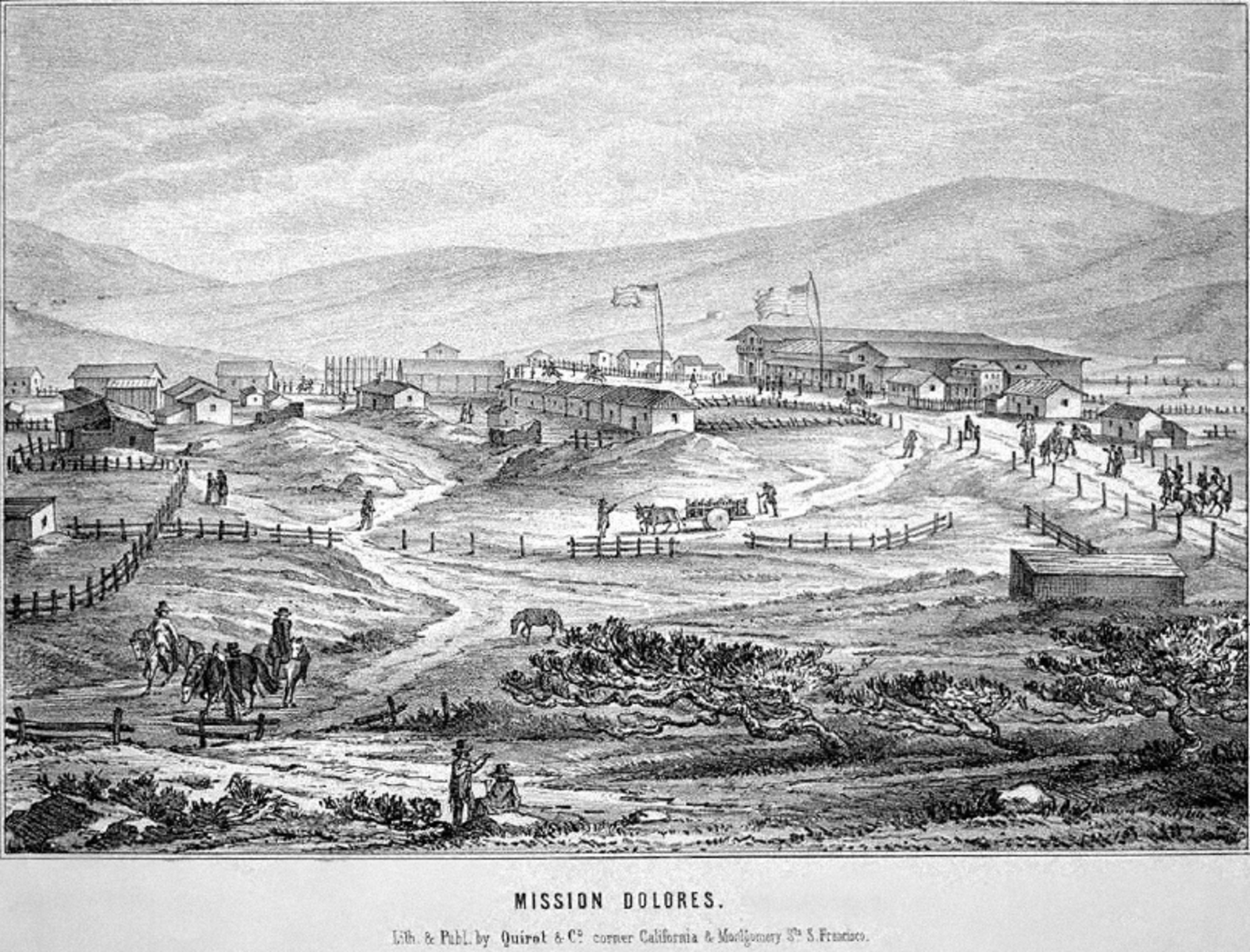

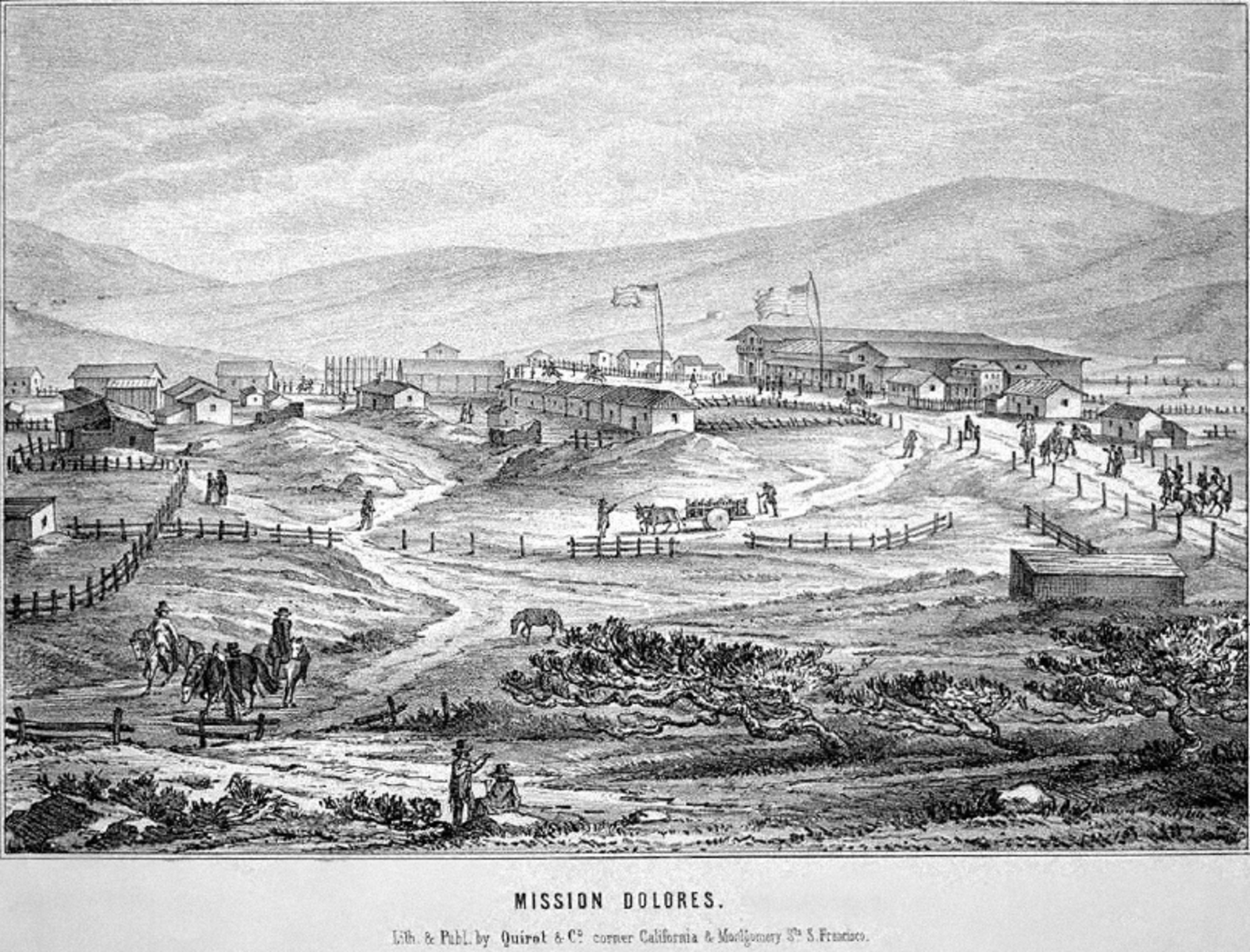

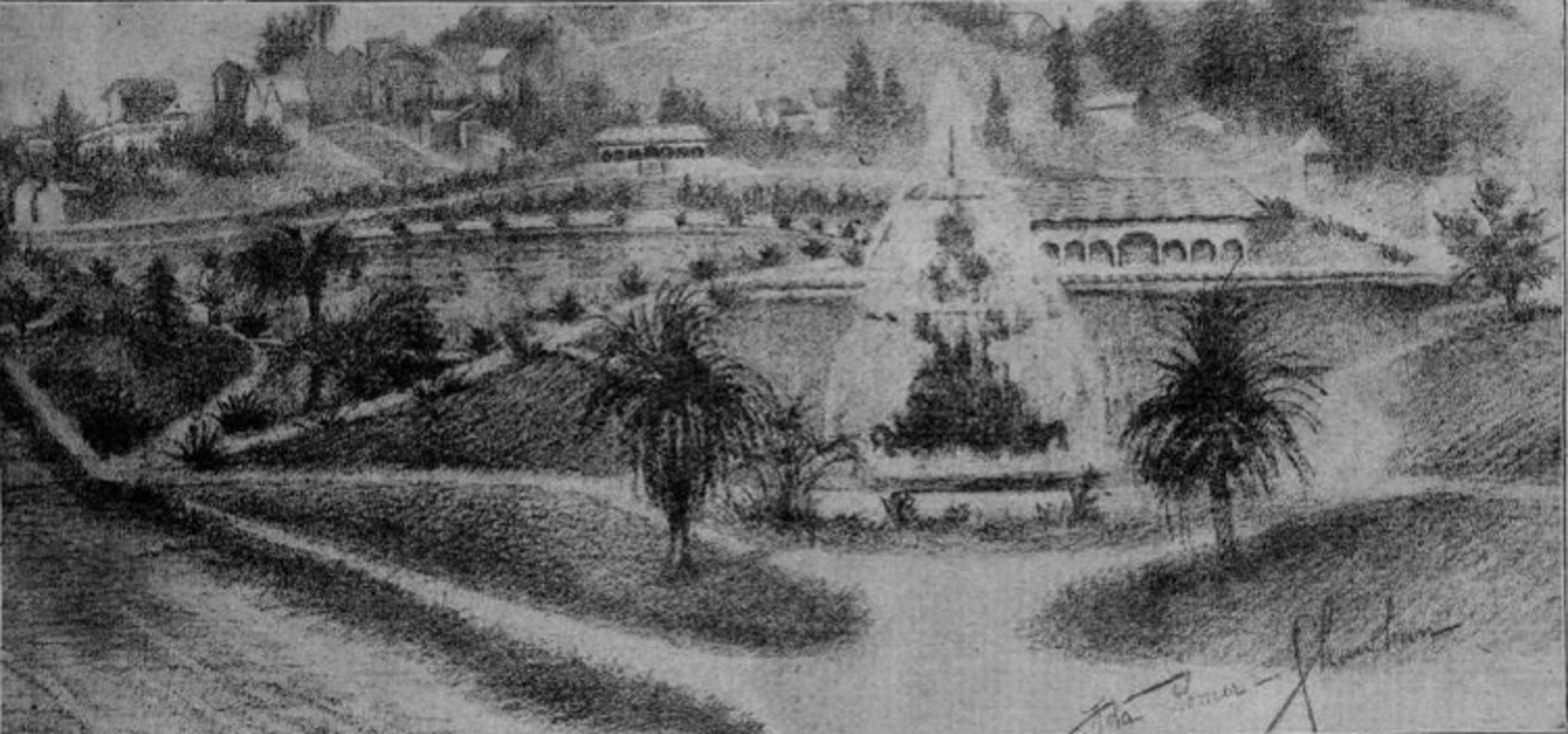

An idealized illustration of the Mission Dolores area circa 1840. View is southwest toward Twin Peaks. Courtesy of the Bancroft Library through the OAC digital collection.

If you didn't make it out to the Dolores Park Meet-up last night, you certainly missed out. First off, it's the only DP 'community meeting' I've ever attended in which no one yelled, which seems like a step in the right direction. But perhaps the most exciting development is that officials from the Neighborhood Parks Council and Rec & Park are beginning to refer to buying weed truffles and getting drunk in the park as a good thing. The overall attitude from the attendees is that the NIMBY's and neighbors have come to terms with the fact that Dolores Park is a drug and public drinking green zone a la The Wire season 3 (although I'm sure Mission Station would beg to differ). The main priorities at this point are just to maximize the cleanliness of the park (no trash/cigarette butts left behind) and do something about the bathrooms. Unlike past community meetings, there was zero talk of ending the party. An age of civility is upon us!

However, the most interesting part of the meeting was the presentation by Peter Lewis of The Mission Dolores Neighborhood Association, which has been referred to as “San Francisco’s version of the Taliban”, for their NIMBYesque activism. The middle of his presentation, which was unfortunately full of the words “we will oppose changing this” when discussing the renovation, was packed full of old photos and plans for the park that I've never seen before. When I asked Peter after the meeting where he dug up all the old snaps, he began to describe an elaborate maze of broken government websites and PDFs. That's right. P.D.F. files.

Because old people are bad at the internet, I've done my best to dig up those old photos and give them a little historical context. Please note that I don't want to spend all day doing this, so I have often blockquoted, at length, excerpts from the horribly long “Mission Dolores Neighborhood Survey.” I know this is academically taboo, but I don't really care. Enjoy:

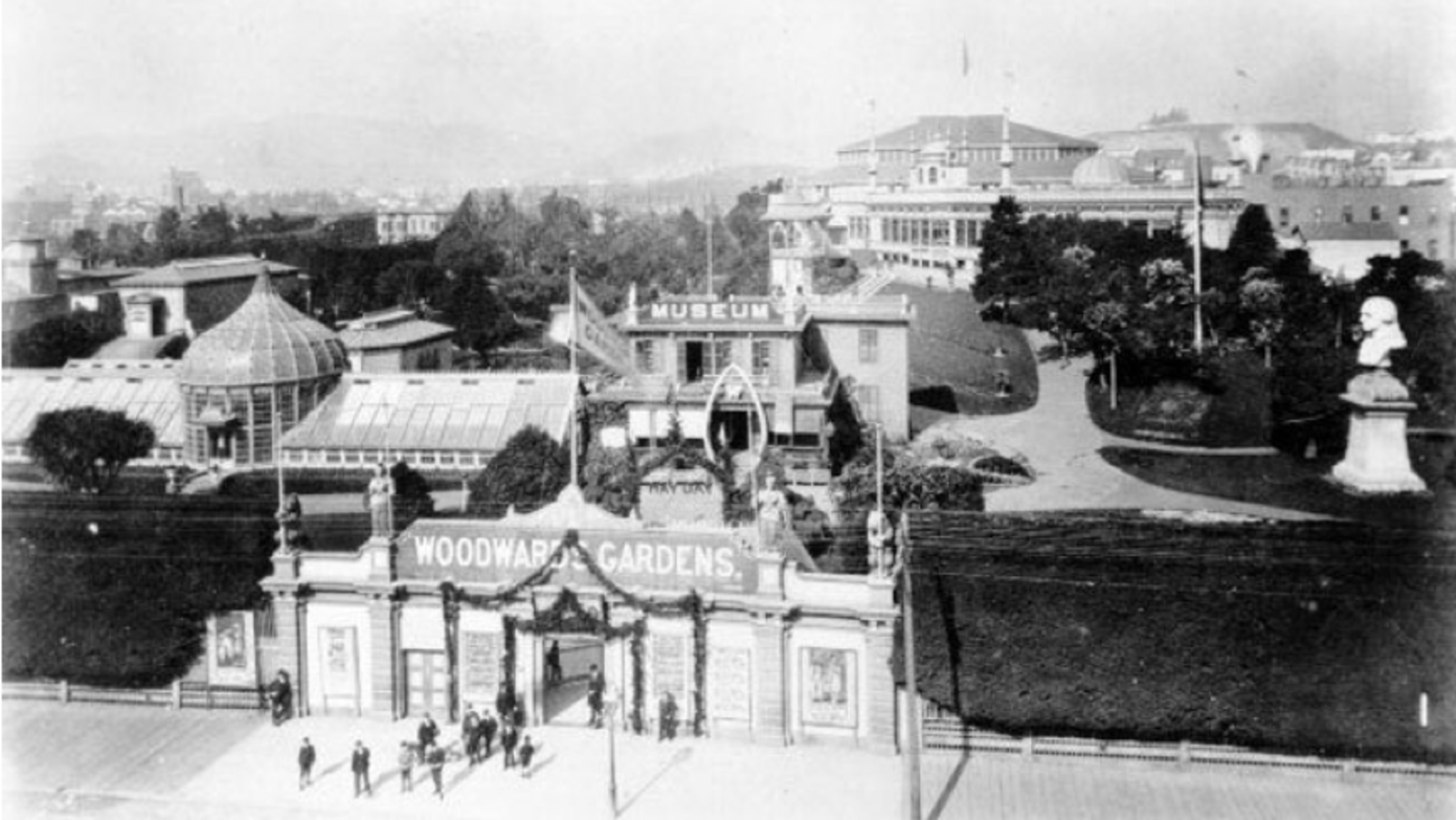

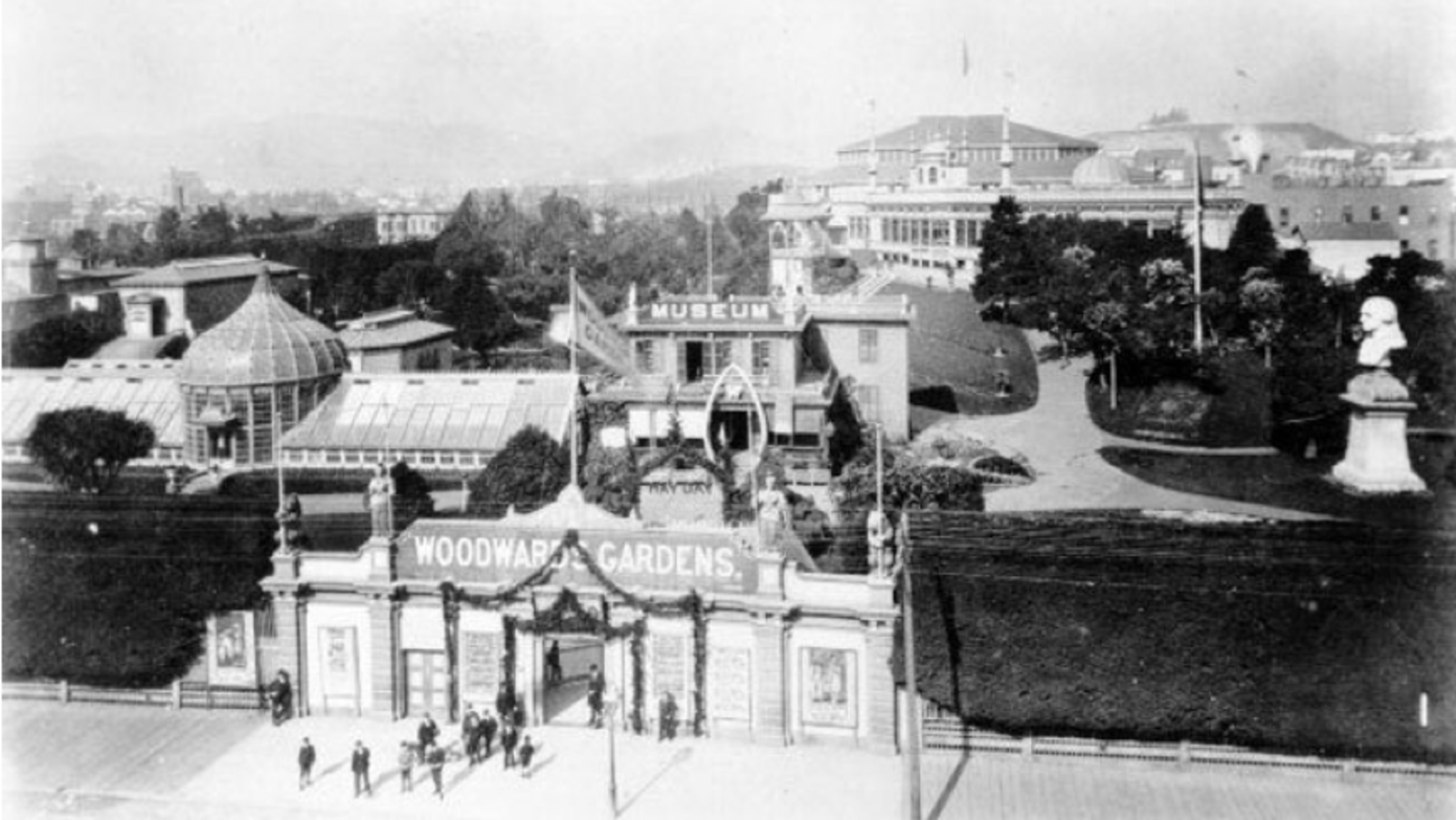

The entrance to Woodward’s Gardens was located on Mission Street. The grounds were bounded by Mission Street, 14th Street, Duboce Street, and Valencia Street, just on the eastern edge of the Mission Dolores neighborhood. Courtesy of San Francisco Public Library.

Prior to Dolores Park, San Franciscans got into trouble through organized chaos and commercial establishments throughout the city (the most famous example of this is Sutro Baths). While documenting the Gold Rush days in 1853, Frank Soule described the neighborhood as a home to bear fights and duels:

The mission has always been a favorite place of amusement to the citizens of San Francisco. Here, in the early days of the city, exhibitions of bull and bear fights frequently took place, which attracted great crowds; and here, also, were numerous duels fought, which drew nearly as many idlers to view them. At present, there are two race-courses in the neighborhood, and a large number of drinking-houses.

At this time, city parks were particularly uncommon. For example, San Francisco only had four parks—Portsmouth, Washington, Union, and Columbia Squares—and NYC's Central Park was not even planned until 1858. Access to the outdoors was limited to commercial venues, which is why in 1866, hotelier and temperance advocate Robert Woodward opened “Woodward's Gardens” to the public at 14th and Mission. Serving as venue for people to enjoy themselves as a virutously alternative to the bear fights and duels, his promotionaly literature descibed the gardens as “The Central Park of the Pacific embracing a marine aquarium, museum, art galleries, conservatories, menagerie, whale pond, amphitheatre, and skating rink – the Eden of the West! – Unequaled and Unrivaled on the American Continent.”

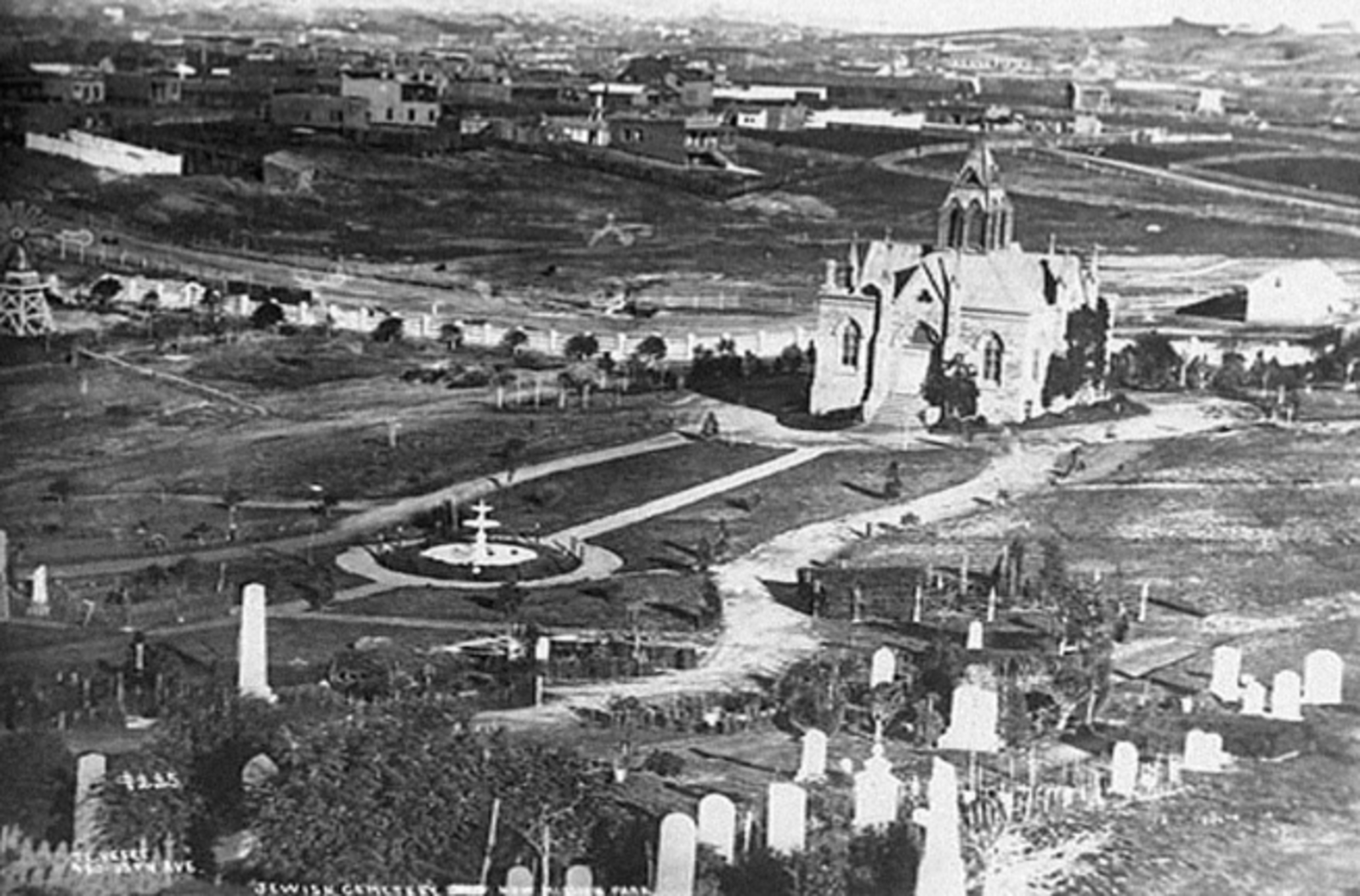

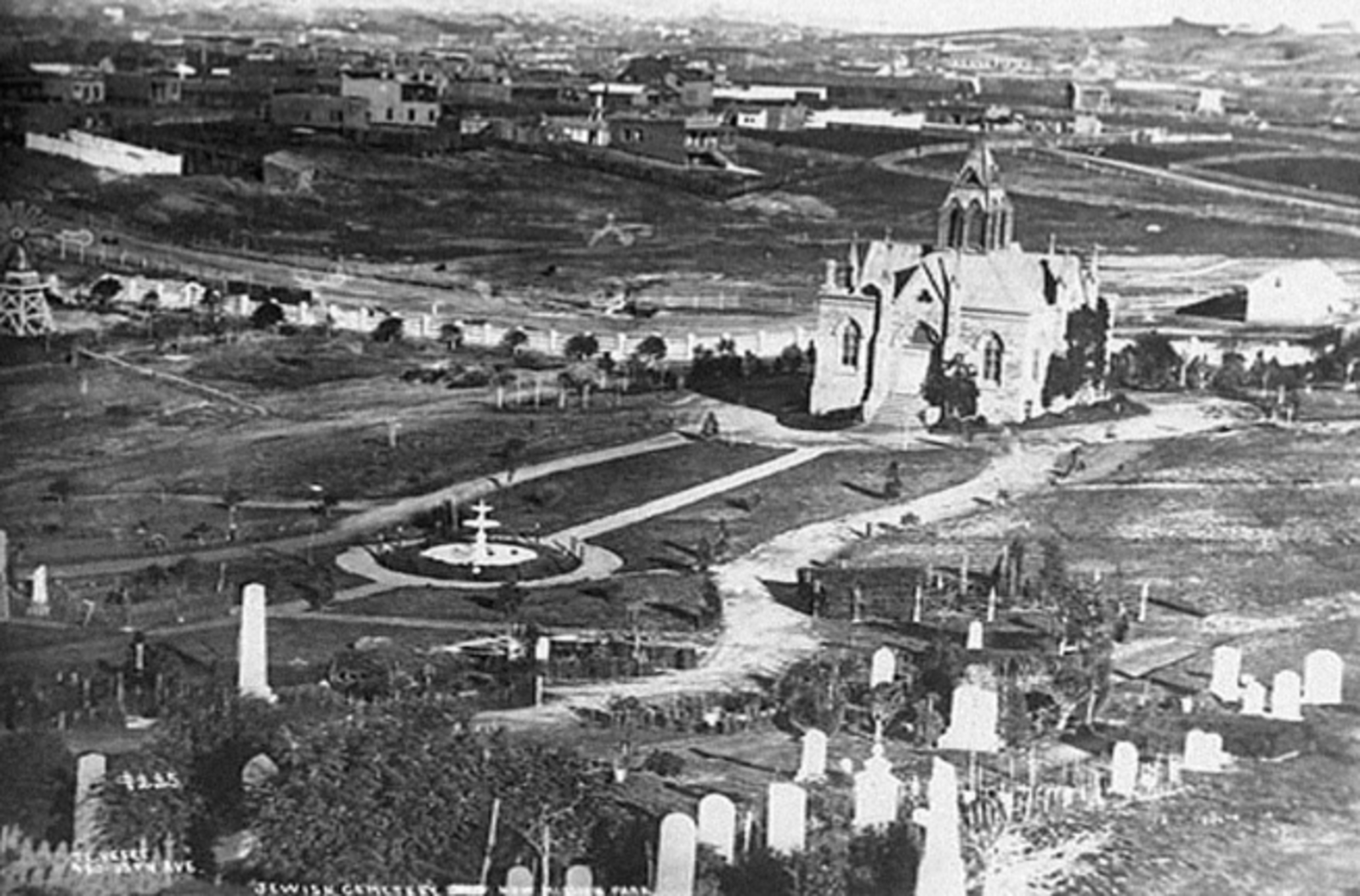

An 1876 photograph of the Jewish Cemeteries, now Dolores Park. Courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library.

Unfortunately the Gardens closed in 1894, leaving the neighborhood with no solid access to a world-class outdoor recreational space. However, in 1880, the city passed a resolution banning graveyards in San Francisco to help reduce the pressures of a growing population and limited space. In the vacuum left by Woodward's Gardens, the neighborhood began looking at an old pair of adjacent Jewish cemeteries to build the park:

Discussions about transforming the old Jewish cemeteries into a public park soon commenced. The Mission Park Association organized in 1897 for the purpose of securing improvements to the Mission neighborhood, the most populated but often overlooked neighborhood of the City. Its primary goal was to establish a park of international quality, combined with a zoological exhibit. The Jewish cemeteries were among several sites suggested for the new park. The group met significant opposition to its cause, with popular sentiment deeming such a park unnecessary, an undue burden to taxpayers, and a scam to fill the pockets of greedy real estate developers; Golden Gate Park already served the city’s needs. Mayor James Phelan also opposed calls for investing in a Mission park.

In 1903 the association started a new campaign for the city to purchase the cemetery land and transform it into Mission Park. More than 1,000 property owners from the southern reaches of the city organized to pass a bond measure that secured funds to purchase the former Jewish cemeteries. The bond measure passed overwhelmingly, a beneficiary of the City Beautiful Movement that had taken hold of San Francisco.

The City sold bonds in 1904 to purchase the former Jewish cemeteries and, in February 1905, purchased the land with the promise to its original owners that the site would always remain a place of beauty. After years of delay, development of a park for the Mission District began. In a dramatic change of tone from its position of opposition years earlier, the city vowed to create “one of the most beautiful parks that now adorn San Francisco.”

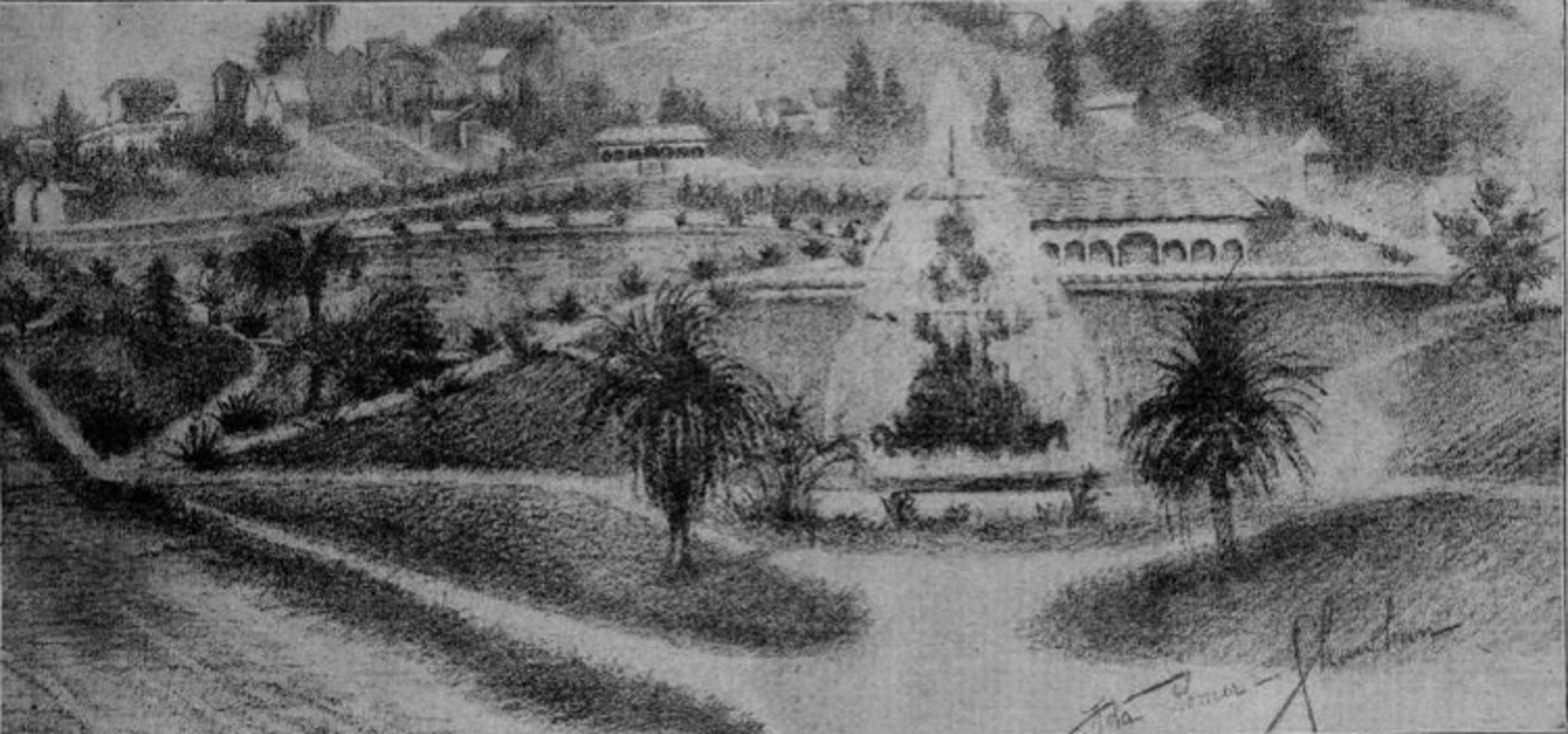

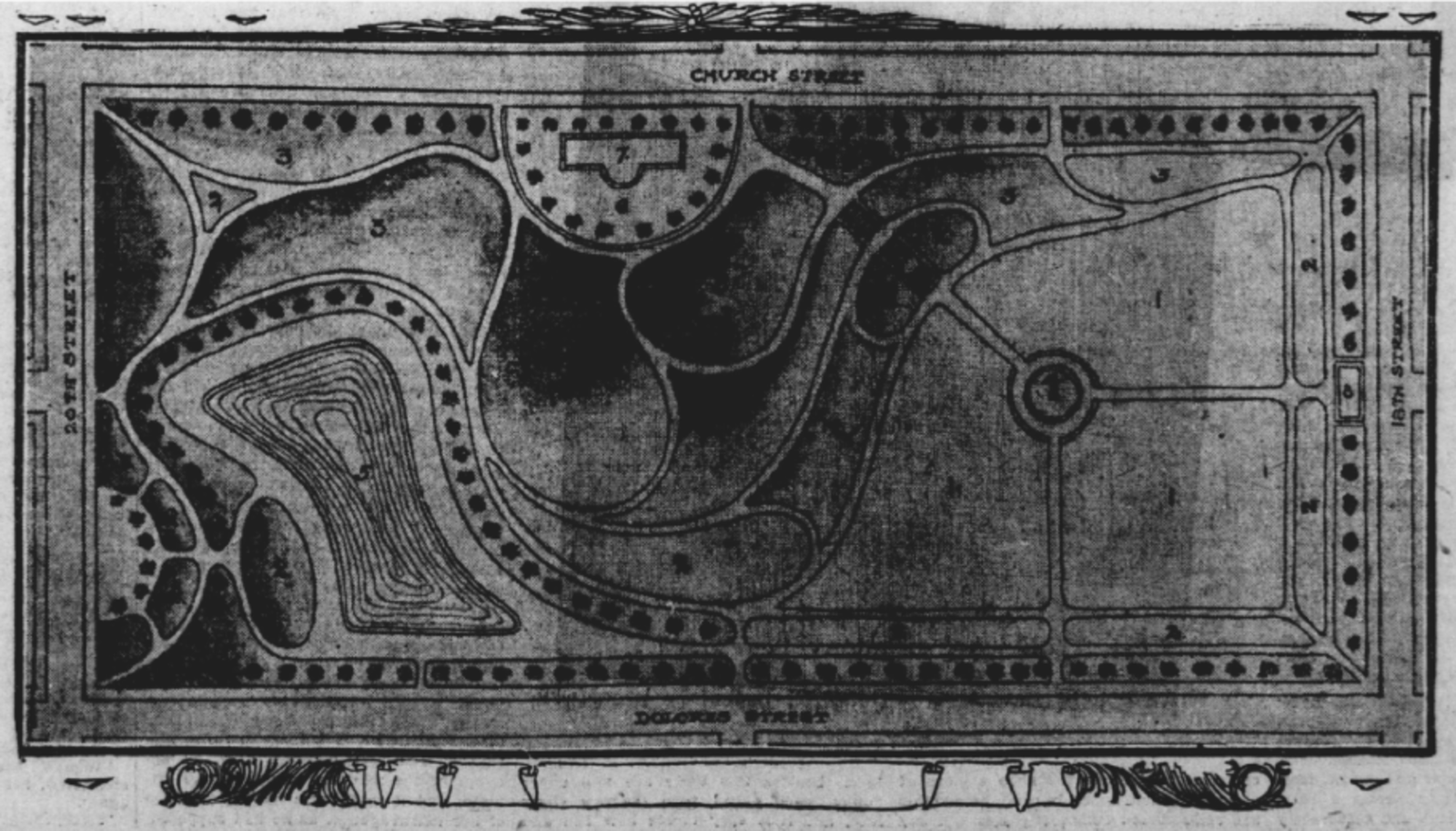

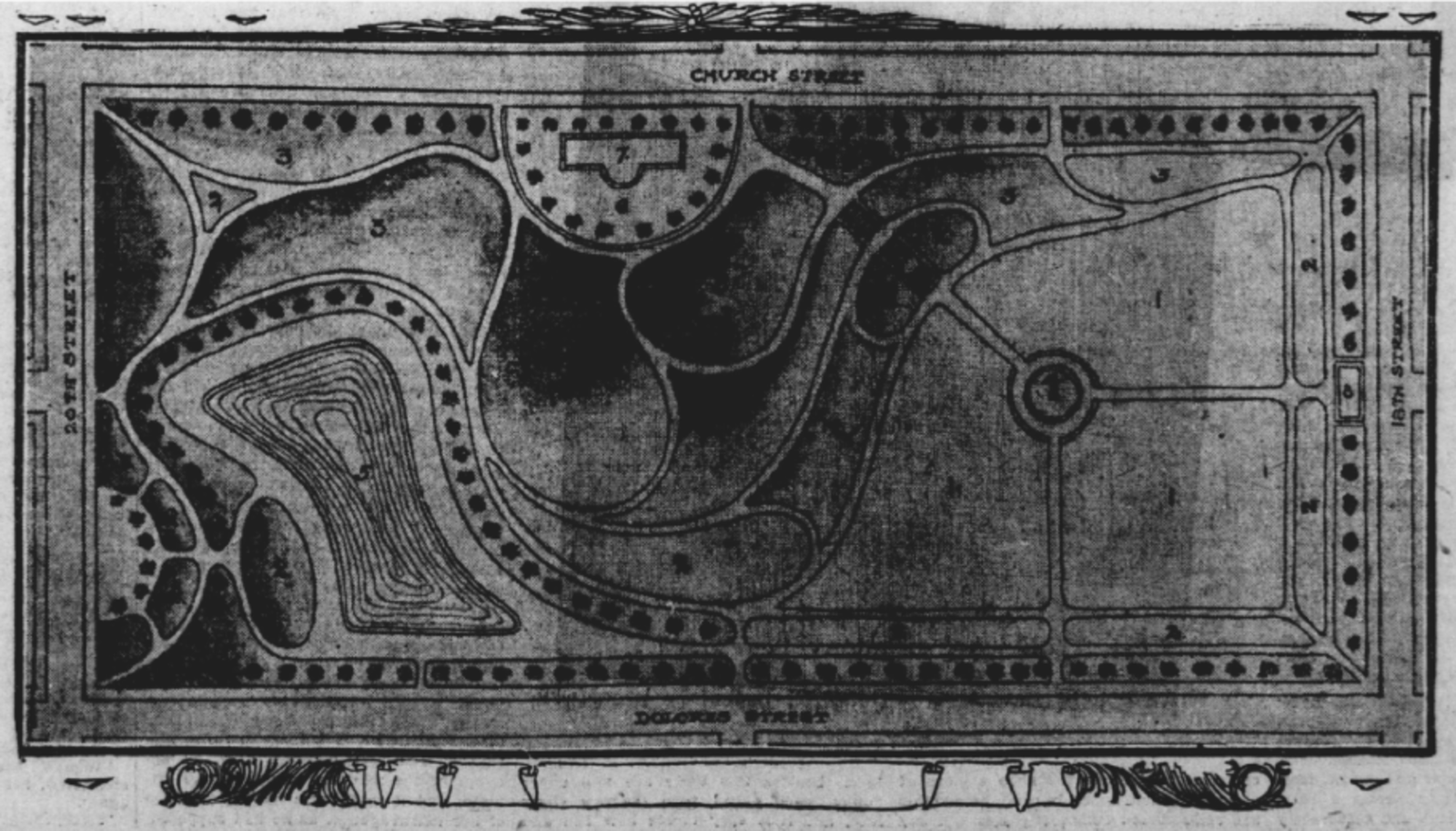

While the city reviewed the plans for a new “Mission Park,” the Barnum and Bailey Circus leased the land and made improvements for its 1905 tour (which incidentally has given us the landscape we see today). After the circus, the city decided on a plan that would involve a garden, swimming pool, and various sports fields. From a 1905 edition of San Francisco Call:

The park will contain a miniature lake 300 by 50 feet, so constructed that children can wade in it in warm weather. A magnificent stone stairway will lead down to the water from Church and Twentieth streets [sic]. On one end of the park a twelve-lap cinder track will be laid, and inside the circle made by it will be erected an outdoor gymnasium.

There will be two tennis courts in the grounds and two baseball grounds. A large bowling green will be laid out in the other section. The Supervisors have been petitioned to have that section of Nineteenth street which runs through the park declared a boulevard. No teams will be permitted to run through it and the block will be made a true boulevard.

The garden effect will be semi-tropical and the entire park stocked with broad leaf plants. A row of palms will border the entire square and an avenue of trees will be planed along the inner edges.

Then the earthquake of 1906 hit and all those plans went to shit as the Park turned into a refugee camp.

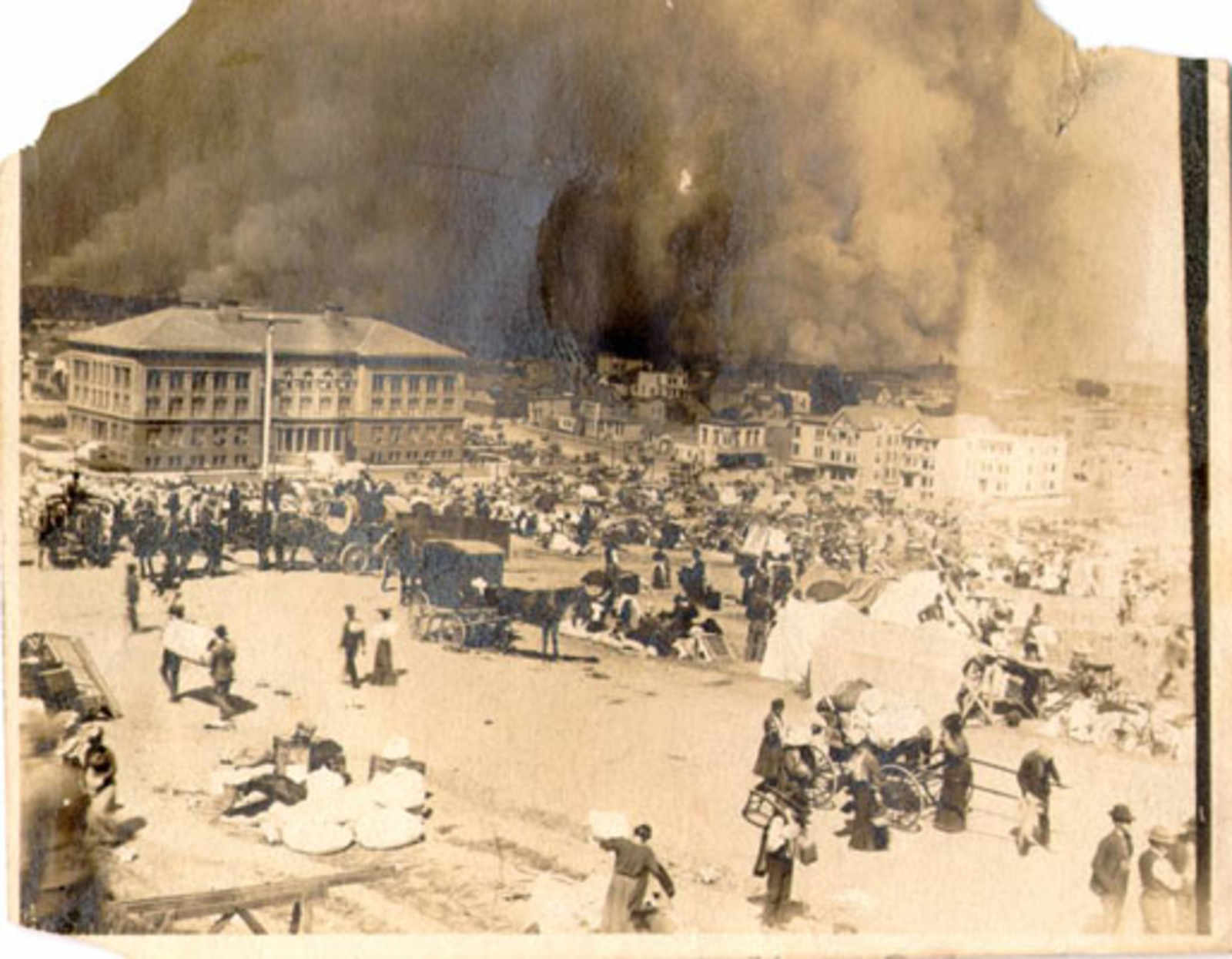

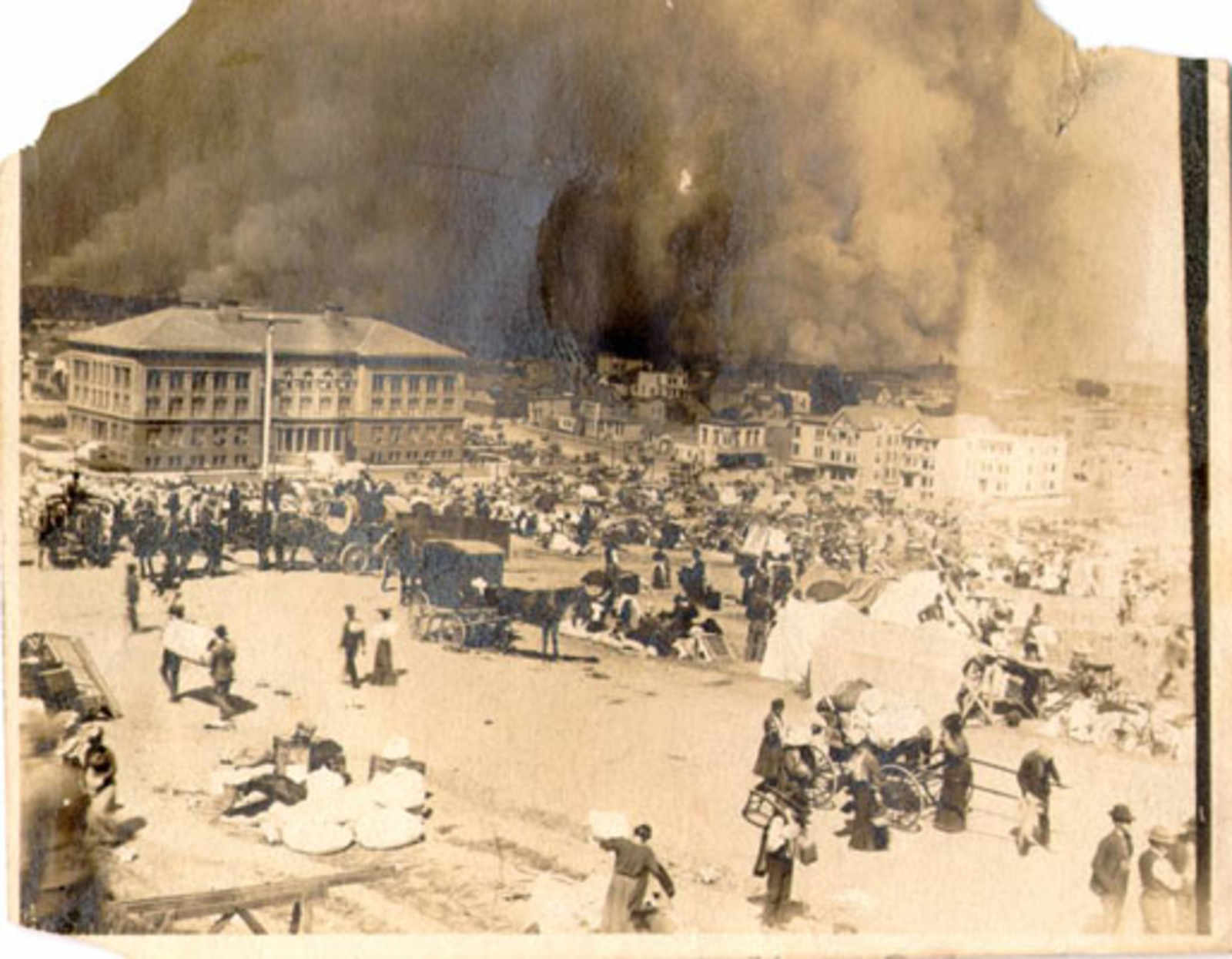

The 1906 fires as seen from Mission Park, looking northeast. Courtesy of Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Mission Park Refuge Camp, 1906. Courtesy SF Public Library.

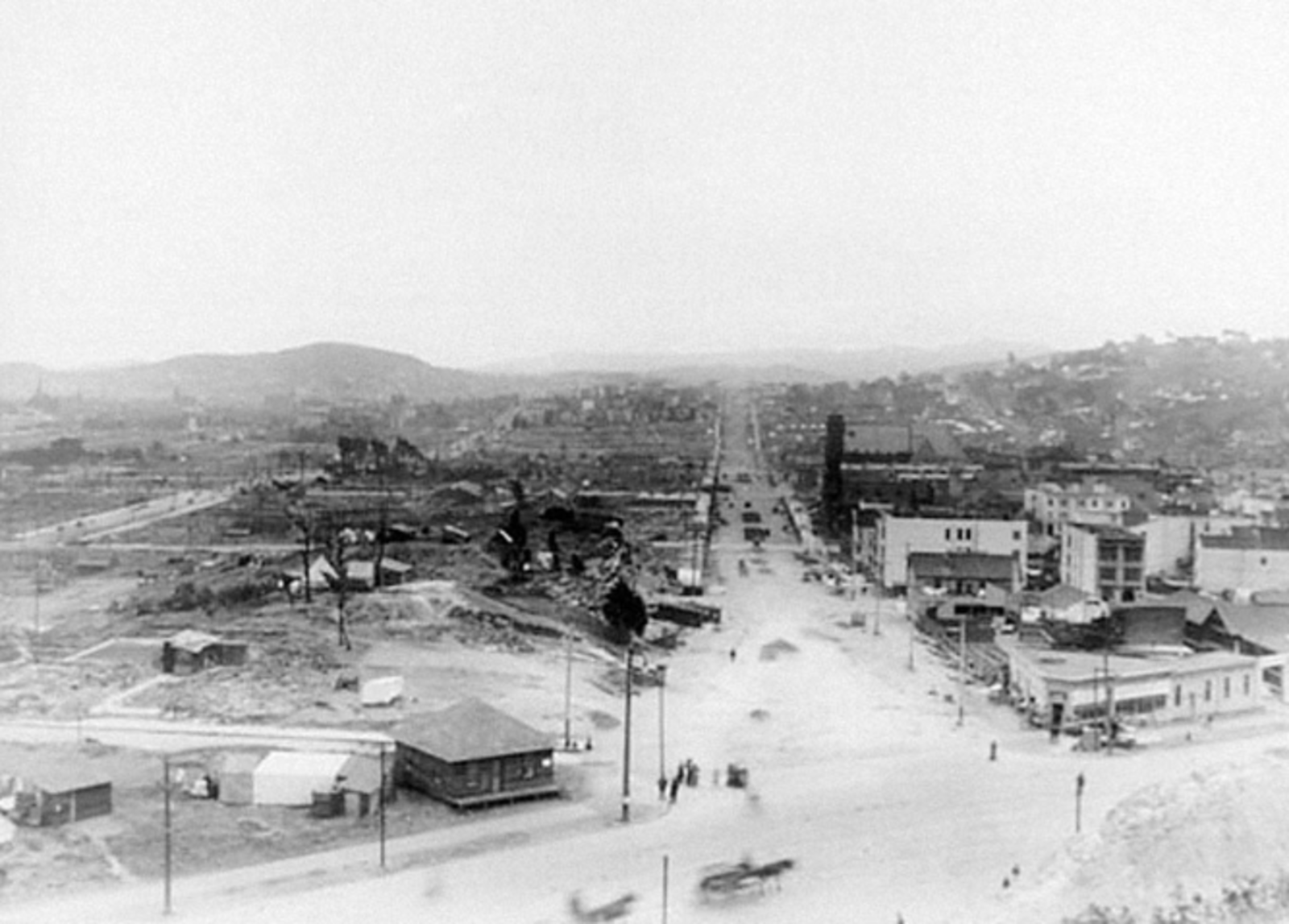

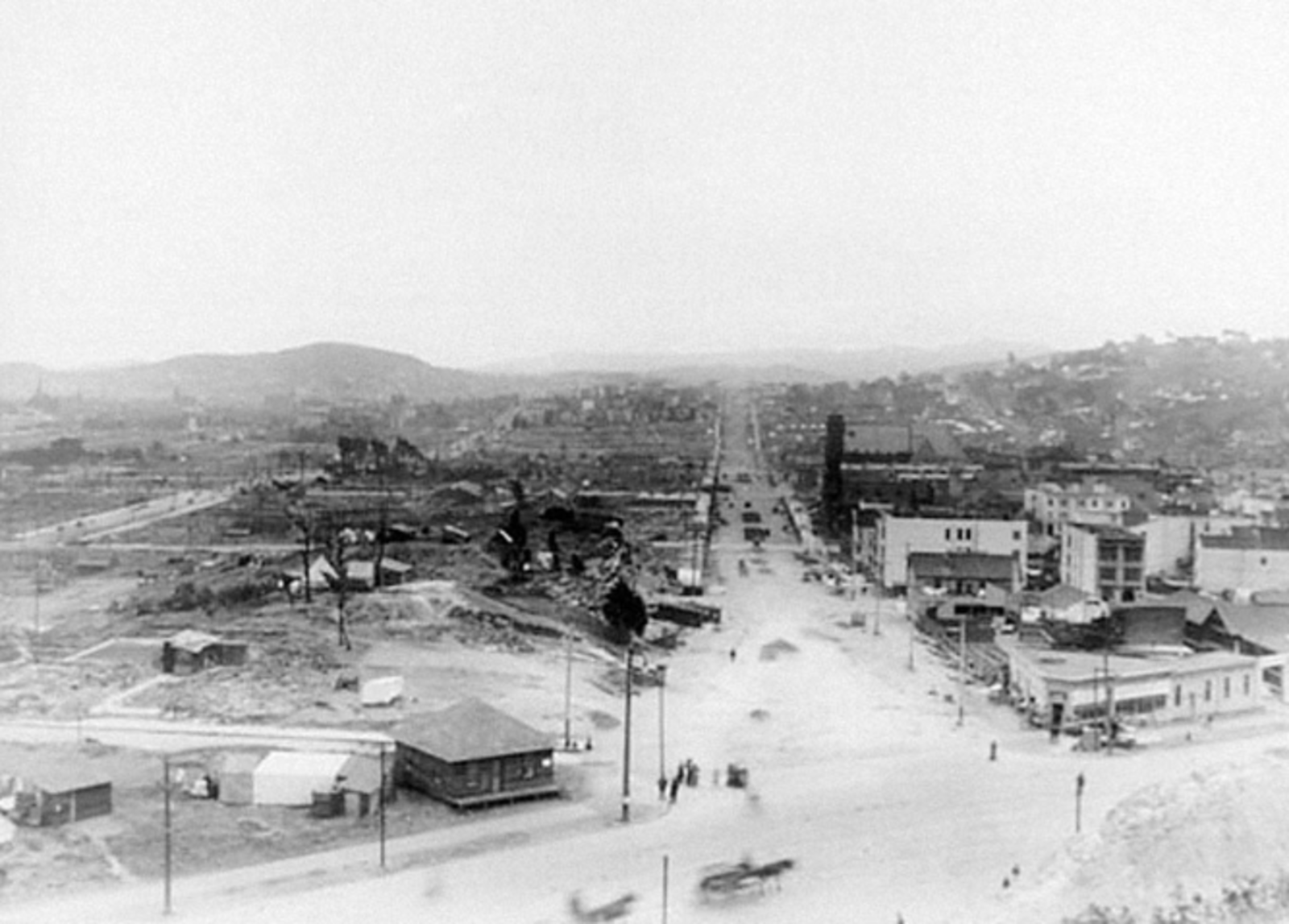

View south down Dolores Street from Market Street after the 1906 earthquake and fires. Courtesy of California State Library.

Mission High School, completed just eight years before the earthquake and fires of 1906, survived the disaster. Here, it overlooks the original, makeshift refugee camp in Mission Park. Courtesy of Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

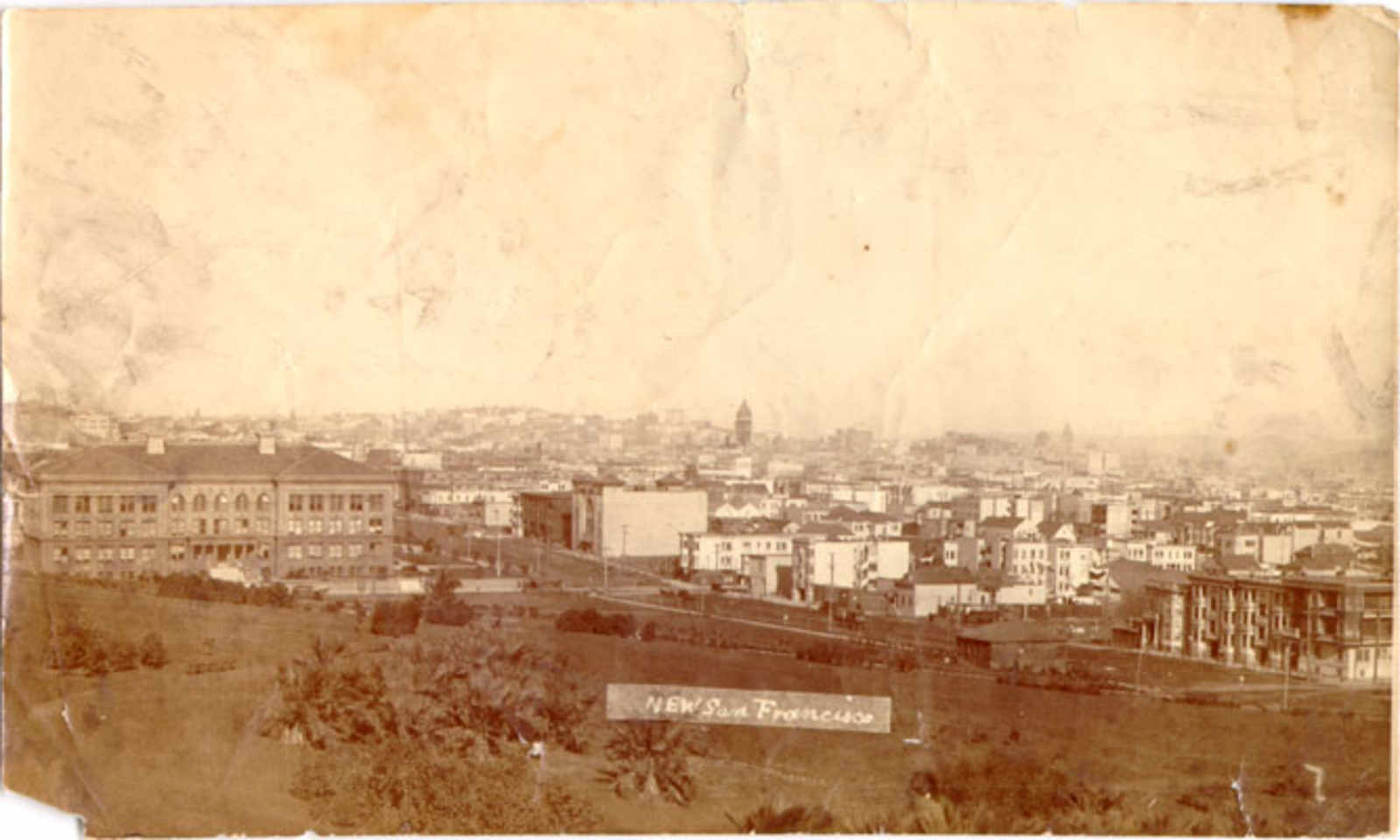

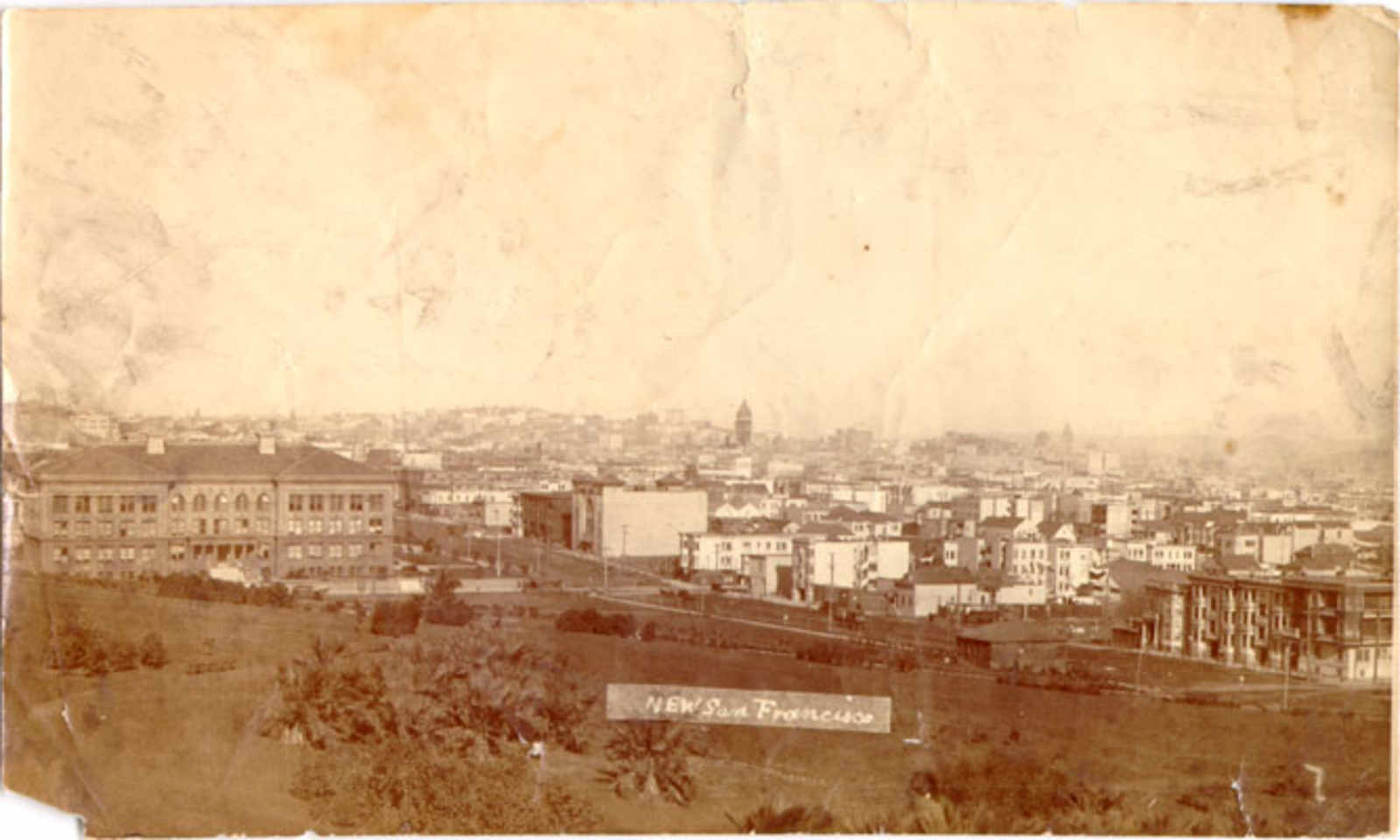

“New San Francisco.” 1909, following the closure of the earthquake refugee parks. Photo Courtesy SF Public Library.

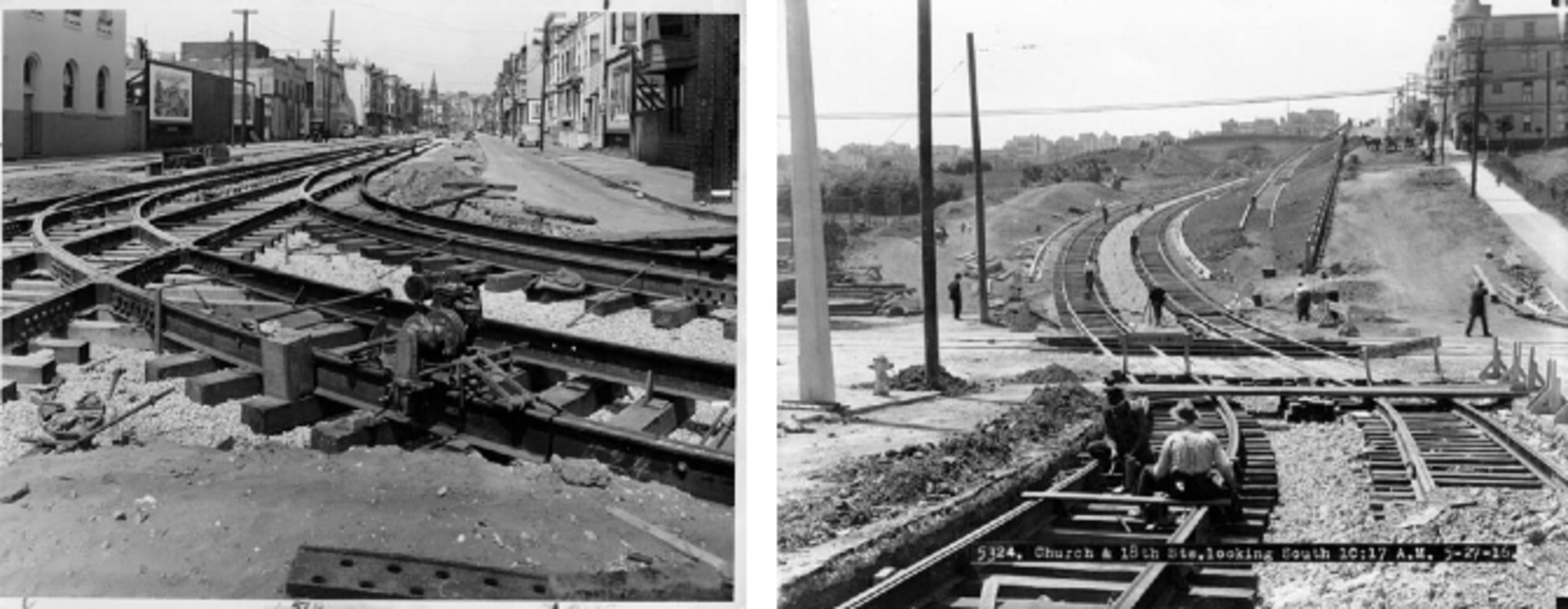

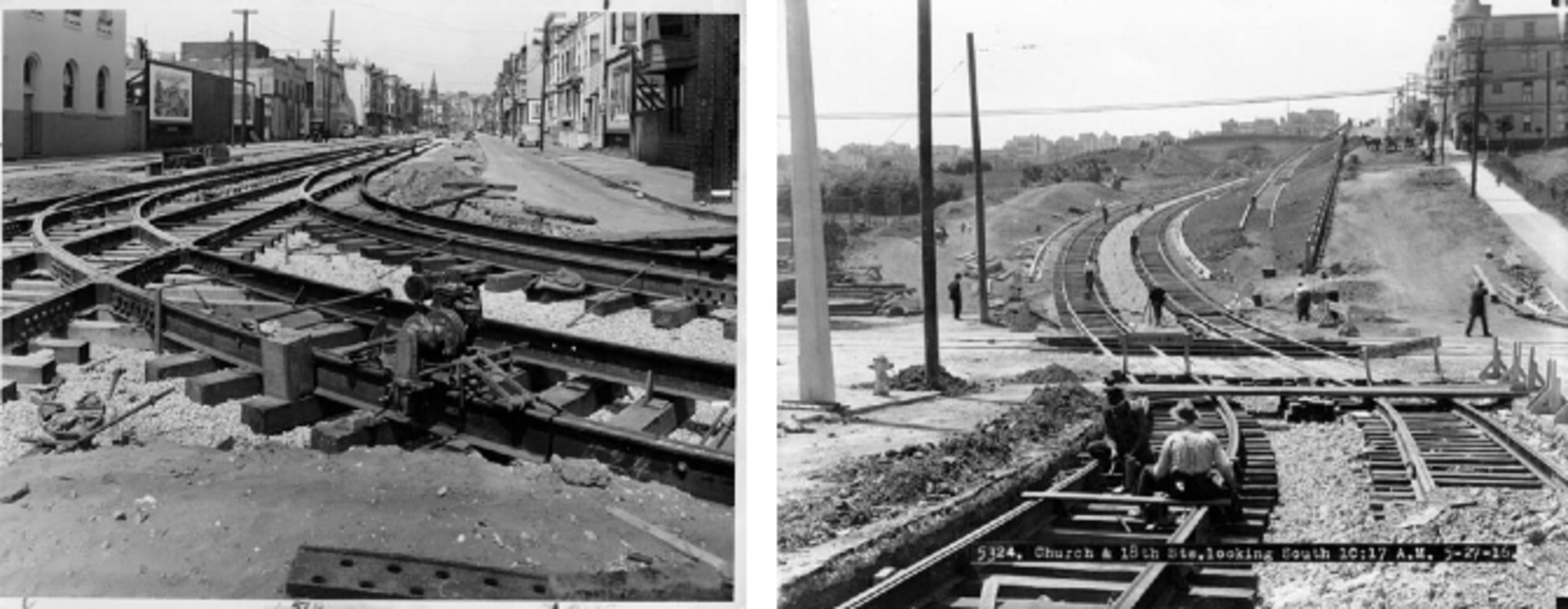

Left: Installation of the Church Street streetcar line at 16th Street and Church Street (looking north). Right: Church Street and 18th Street, looking south towards Mission Dolores Park. The Youth’s Directory is the first building visible. Courtesy of San Francisco Public Library. Photo circa 1916.

Following the earthquake and subsequent fires, the city largely ignored Mission Park, as it needed to focus on rebuilding the city. By 1913, the reconstruction was largely complete, and the city began refocusing on making new infrastructure improvements, including a bond measure to extend the City's railways, including a Church Street rail that we now see in the western side of the Park:

The [Church Street electric streetcar line] marked one of many alterations that Mission Park underwent in the post-disaster period. The City was slow to invest significant funds into the park once the tent city was removed, around 1908. Improvements were limited to laying a new water pipe system, spreading loam and fertilizer over the park, planting some trees and shrubs, and removing macadamized areas that the Red Cross had used during the emergency relief. Crowley Cottage also remained on the park grounds as a reminder of the disaster.

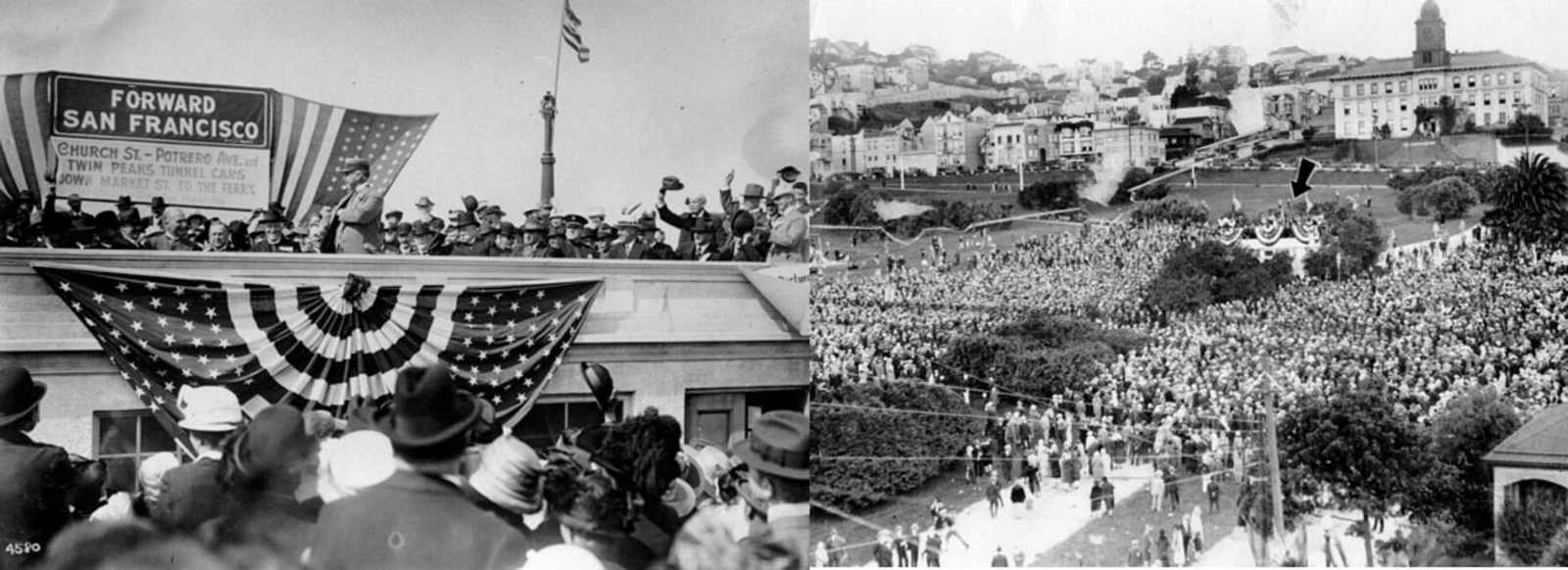

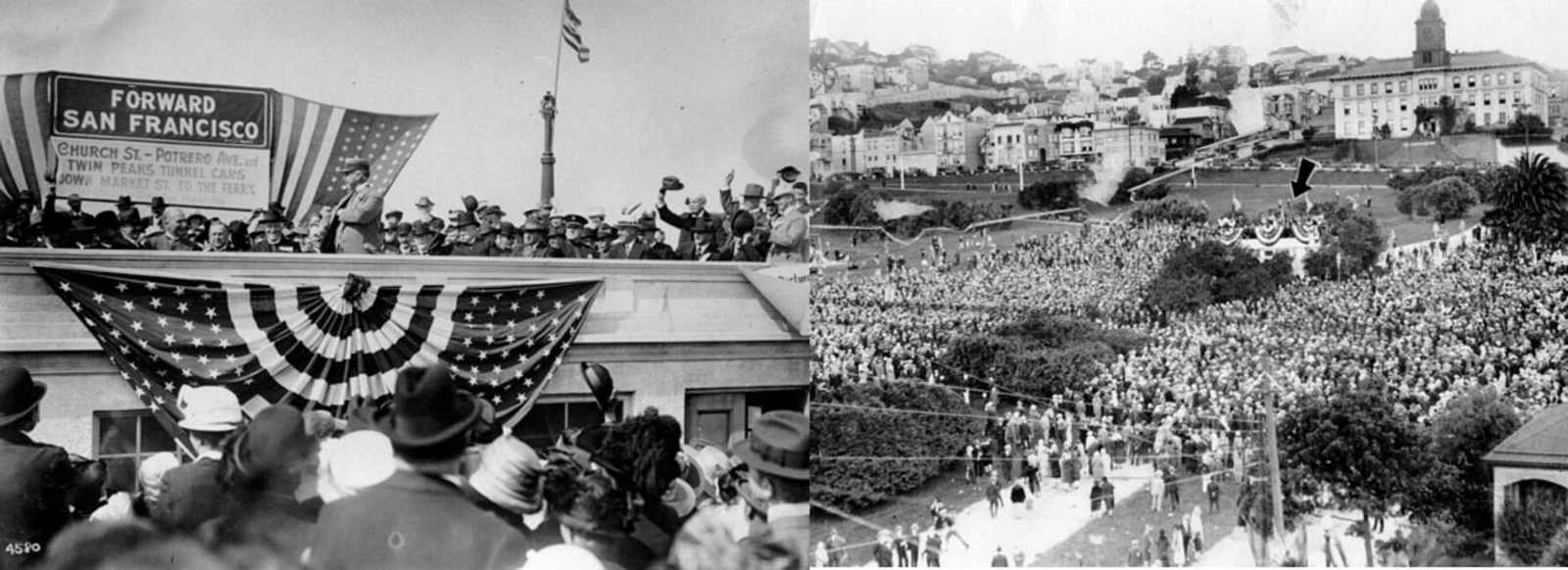

Left: Mayoral Rolph dedicating the newly completed Church St. rail. Aug. 11th, 1917. Right: claimed to be an unrelated rally on Oct. 12 1926 by the SFPL, I'm not so sure. Both photos courtesy SF Public Library.

Mothers and their children at the Mission Park playground in 1922. Courtesy of San Francisco Public Library.

Continued from above:

Improvements to Mission Park continued to occur gradually before World War I, according to no specific plan, and largely in thanks to the untiring efforts of the Mission Promotion Association on Commercial Development. The group called for paving the streets that bordered the park, constructing sidewalks and curbs around the park, and completing the transformation of Dolores Street into a boulevard by adding decorative medians and planting palm trees. Dolores Street from 17th Street to 20th Street was bituminized in 1910 to facilitate smooth passage to and from the park; Dolores Street was also extended south at this time from 20th Street to Mission Street. 1913-1914 saw the construction of a “convenience station” (storage and toilet facilities) designed by M. Shelby Company. The pathway that still bisects Mission Dolores Park was improved to include concrete paths during the 1910s, and tennis courts arrived in 1913. The children’s playground promised in the plan originally approved by the Parks Commission was built in 1916. It replaced a wading pool.

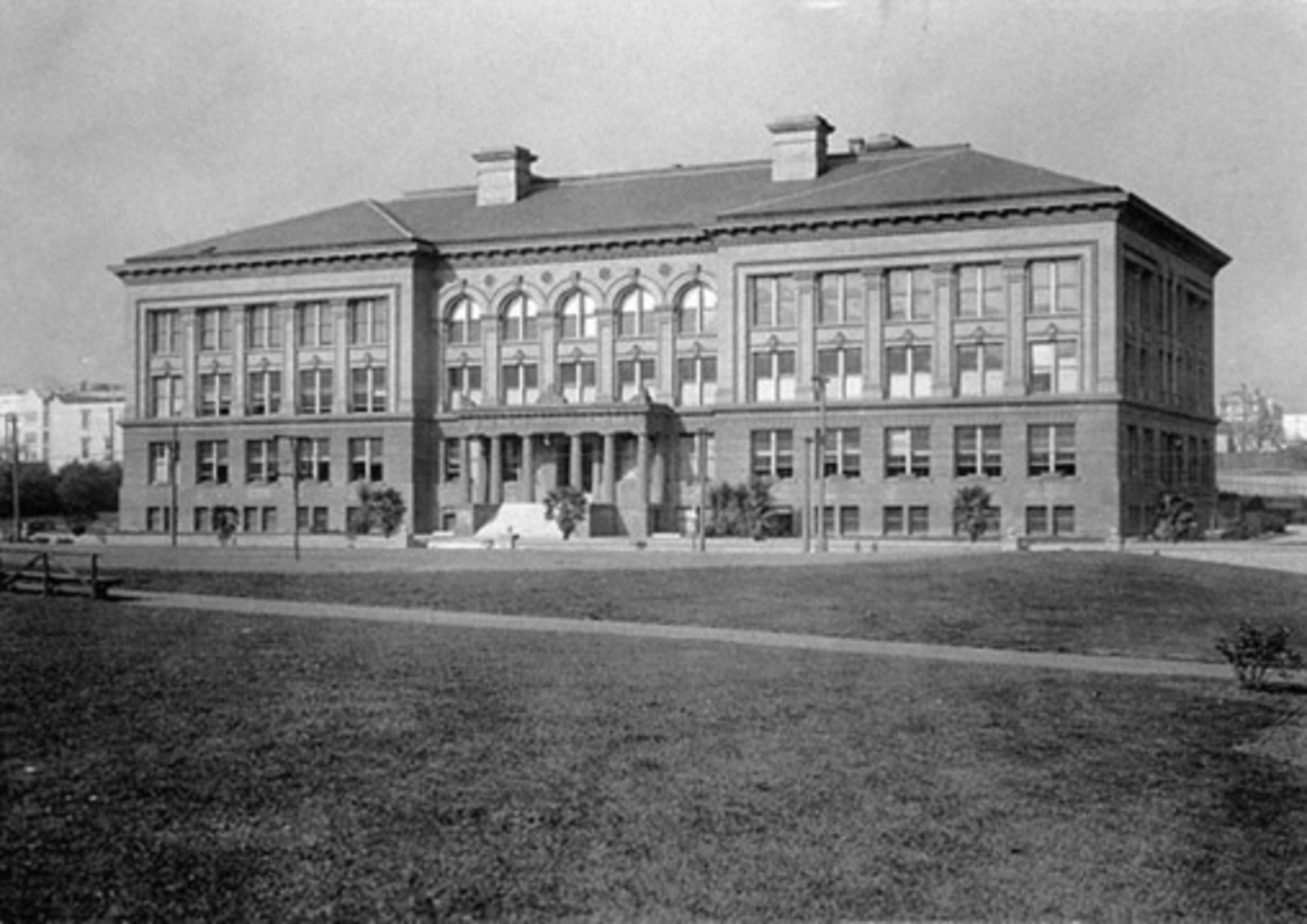

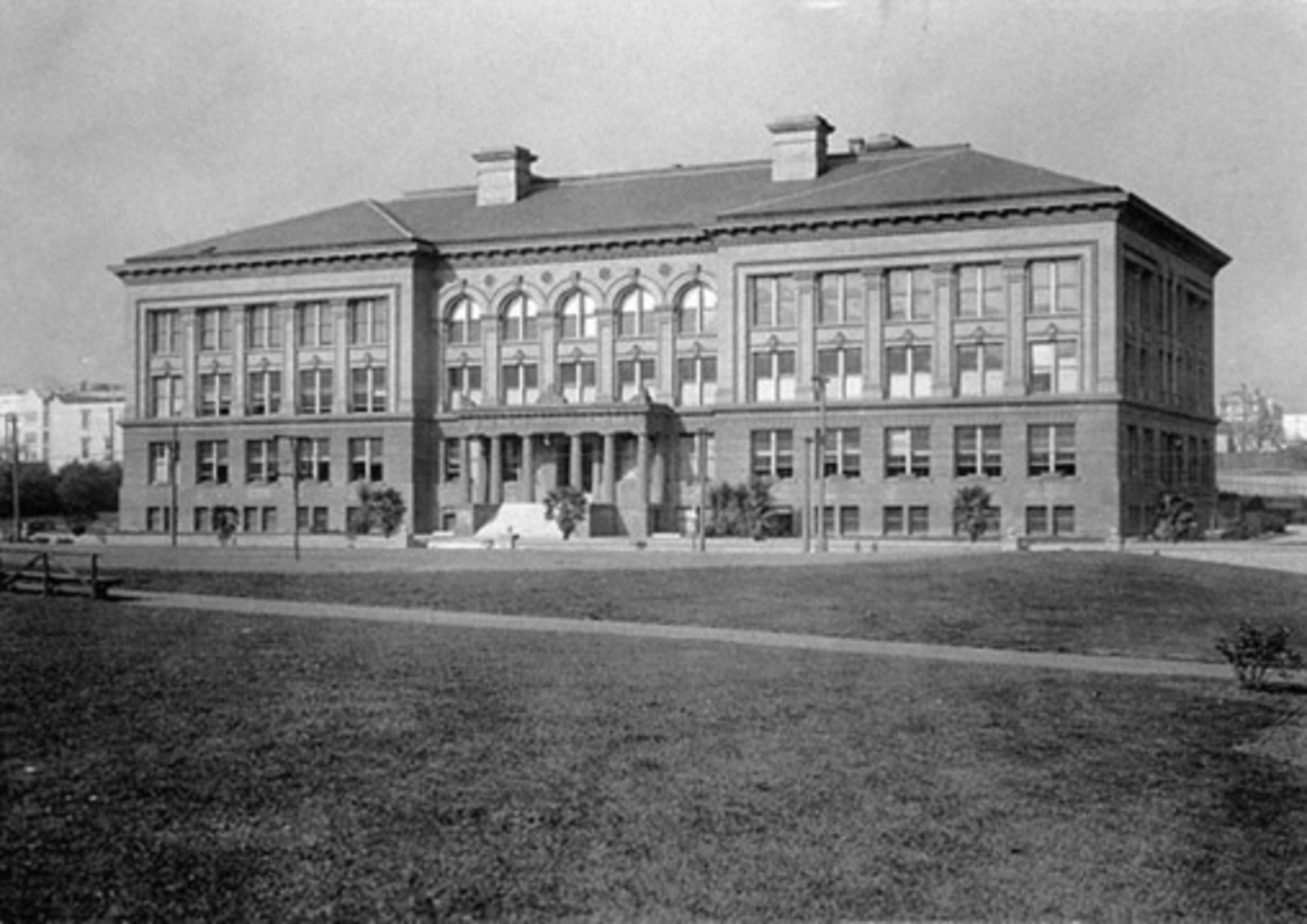

Old Mission High School, built 1897. Courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library.

Around this time, the city also undertook the project of renovating both Mission High School and Everett Middle School. Renovations to Mission High, which sits just to the north of the park was undertaken in 1925, leaving us with the building we now see today.

More photos below. Read the 100 page-long historical survey here (PDF warning).

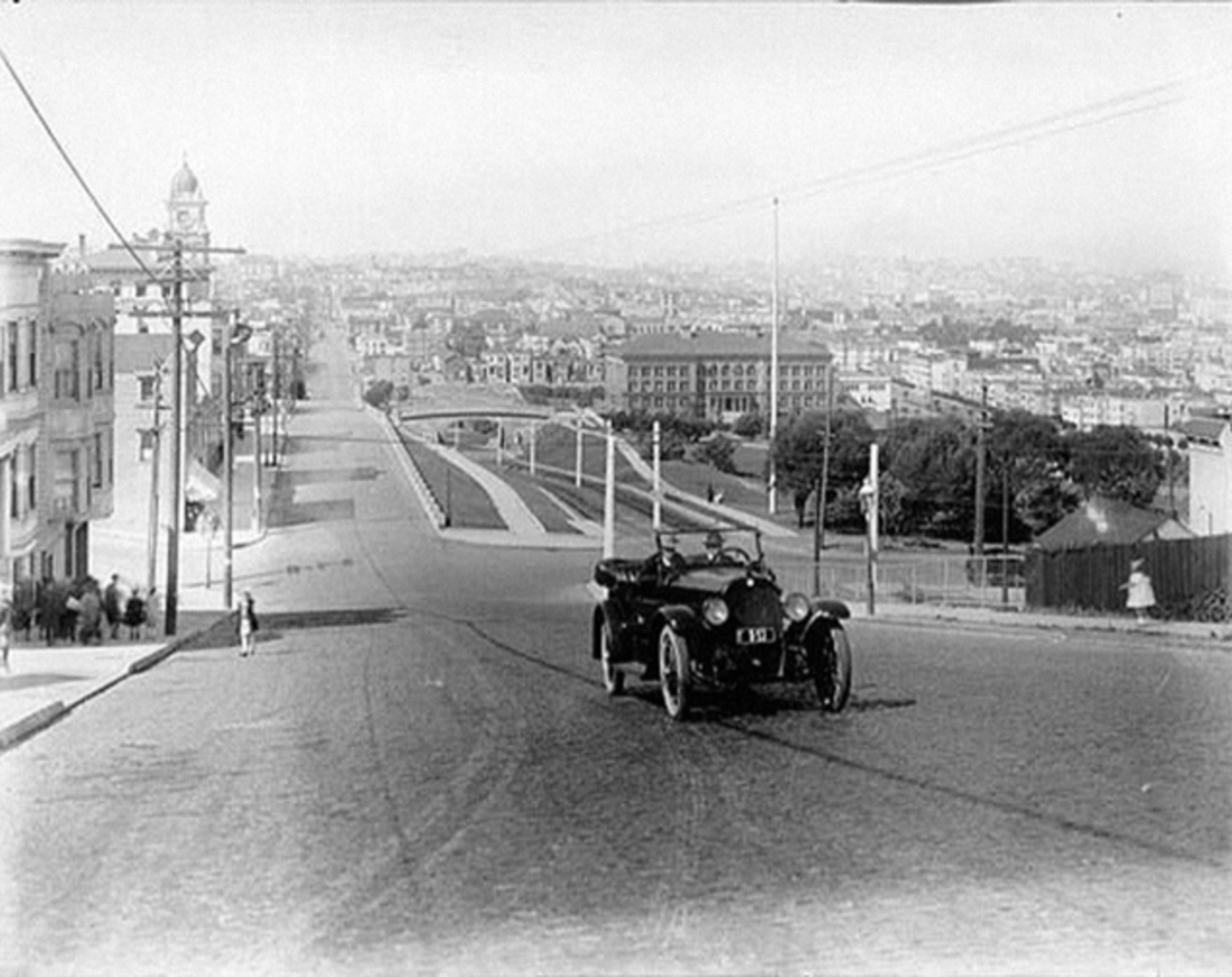

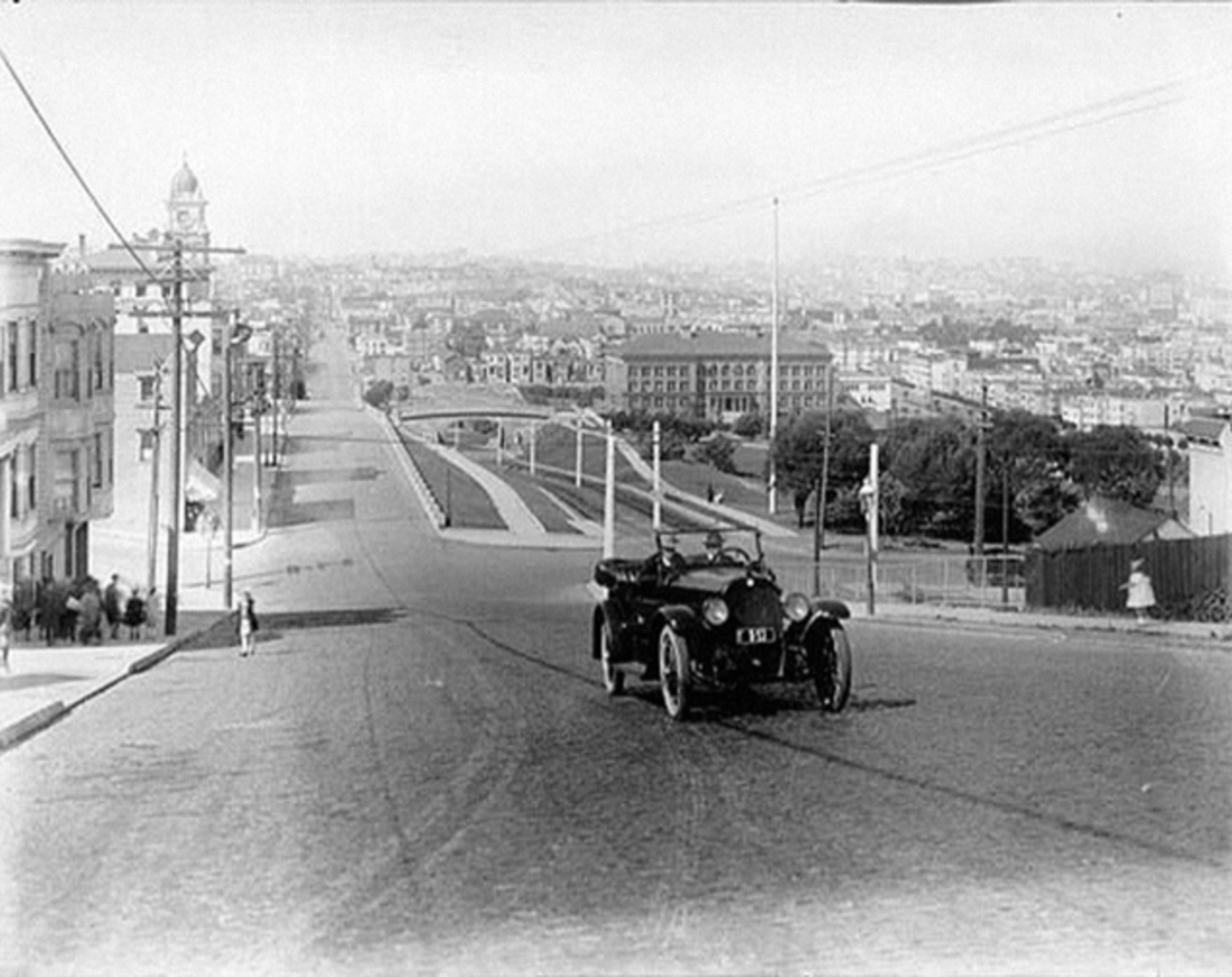

Undated photo between 1916 (installation of the Church St Muni line) and 1925 (Construction of The new Mission High).

View north toward the Mission High School from Dolores Street, circa 1930. Courtesy of San Francisco Public Library.