— By Jackson West (@jacksonwest) |

There are three arguments floating around as to why the rent is too damn high in San Francisco, all of which just happen to serve the interests of local real estate developers:

- San Franciscans make it hard to build!

- Rent control actually causes rents to go up!

- This has been happening since the Gold Rush!

All of these arguments hinge on the assumption that what’s happening right now in the Bay Area generally is somehow unique to San Francisco specifically. This morning, an article about the “yuppification” of San Francisco from the L.A. Times, published in 1985, was making the rounds on Twitter, and plenty of people making these arguments have cited it as proof of one, or all, of the above. It certainly does sound familiar!

Whatever its name, its result is spiraling housing costs, clogged traffic, an exodus of middle-class and poor families and declining black and Latino populations. And the trend seems certain to continue despite a new effort by the city to limit growth, restrain housing costs and preserve neighborhoods.

But it doesn’t just sound familiar to San Franciscans, because it’s happening all over the country.

It’s true that by 1985, the impact of the de-industrialization of American cities and increasing income inequality was first starting to reshape the streets and skyline, helped in no small part locally by then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein (who’s husband, incidentally, is investment banker Richard Blum, chairman of the board of commercial real estate developer CB Richard Ellis). Not to mention the economic policies of the Reagan administration, neo-liberalism’s legendary benefactor and hero. Economic policies which have thrived through the following Republican and Democrat administrations, including the current one.

What is new is that it’s accelerating. And as the divide between the haves and have-nots grows larger, the haves are concentrating their wealth and the have-nots are either clinging to ever-more-precarious perches on the one hand and following the money in a desperate search for economic opportunity on the other.

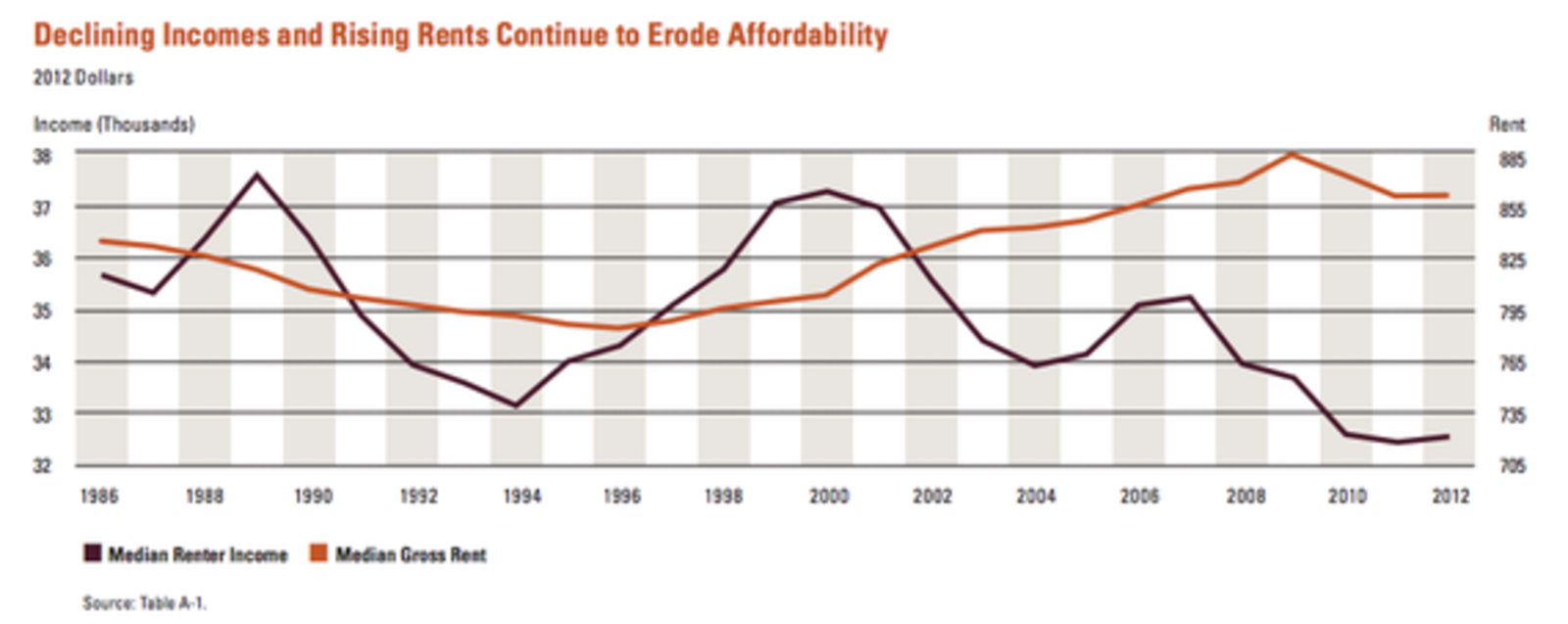

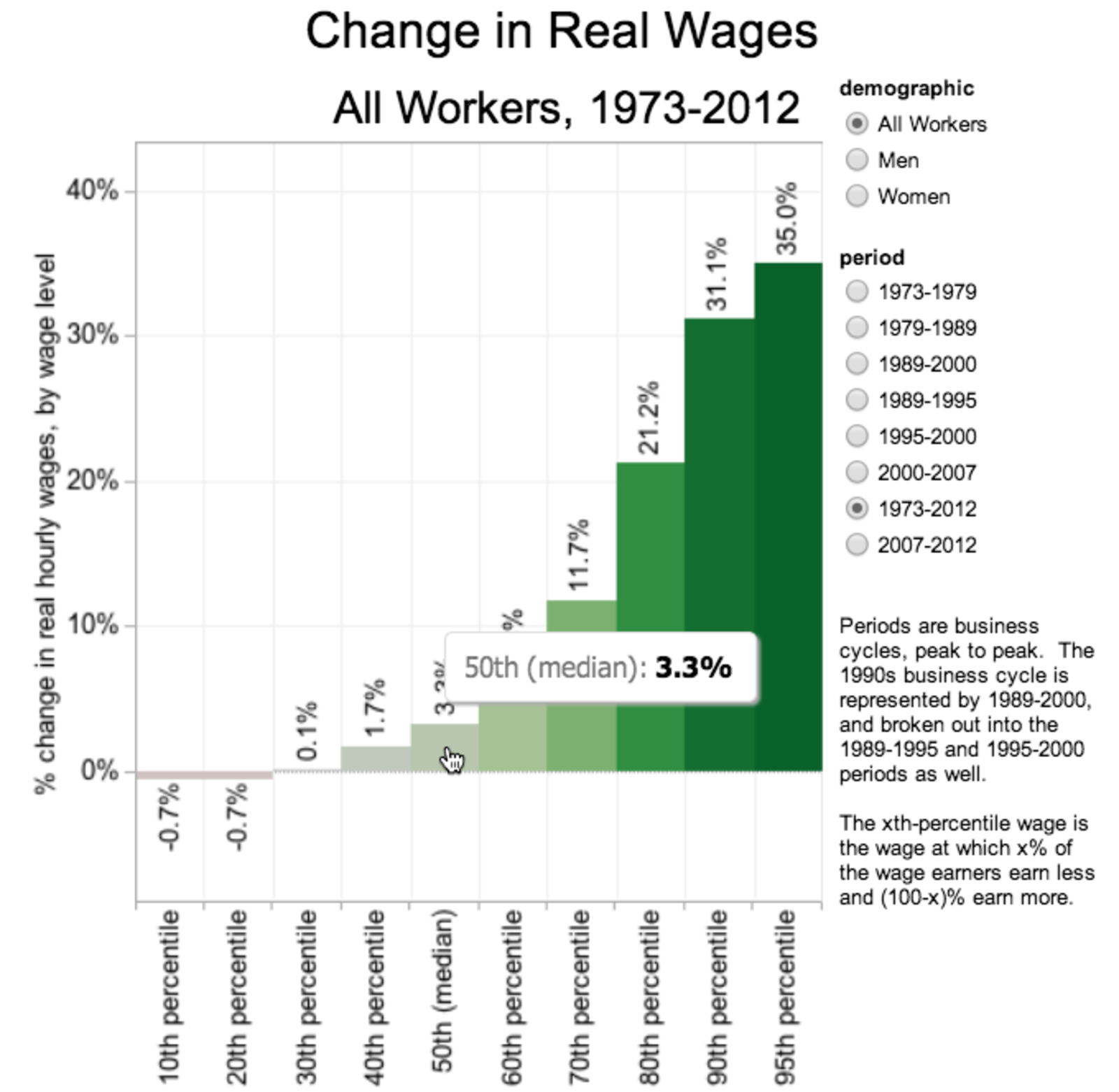

Earlier this week, Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York, a blog which documents the passing of that city’s urban institutions, populations and traditions, published a lengthy article on, frankly, Manhattanization, partly in response to Spike Lee’s recent remarks on what’s happened to the Fort Greene, Brooklyn neighborhood of his youth. It’s as colorful an illustration on the impacts of real wage decline since the 1970s as the above graphs.

Many New Yorkers today, across racial and class lines, do wish for old-fashioned gentrification, that slow, sporadic process with both positive and negative effects—making depressed and dangerous neighborhoods safer and more liveable, while displacing a portion of the working-class and poor residents. At its best, gentrification blended neighborhoods, creating a cultural mix. It put fresh fruits and vegetables in the corner grocer’s crates. It gave people jobs and exposed them to different cultures. At its worst, gentrification destroyed networks of communities, tore families apart, and uprooted lives. Still, that was nothing compared to what we have today.

I want to make one thing clear: Gentrification is over. It’s gone. And it’s been gone since the dawn of the twenty-first century. Gentrification itself has been gentrified, pushed out of the city and vanished. I don’t even like to call it gentrification, a word that obscures the truth of our current reality. I call it hyper-gentrification.

If you want a window into what that earlier era of gentrification looked like, Mission Local also reached back to their archives for an interview with author Michelle Tea about her experience moving to San Francisco in the early 90s (shortly after the Loma Prieta earthquake momentarily relieved pressure on the San Andreas fault, population in-migration, and real estate prices).

Mission Local: Why did you move to the Mission?Michelle Tea: It’s not that it was a particularly cool neighborhood, although I later found out that it was. This is just where the cheap rents were. I moved here in 1993, and when the bus let me off on Valencia, I remember the street felt deserted — like almost all of the storefronts were closed.

But somewhat tragically, wherever artists and activists go, real estate developers tend to follow, often because they lead the artists and activists there in the first place. Before moving to the Bay Area, my apartment in Brooklyn was at Underhill and Washington Avenue in a community largely composed of immigrants from the Carribean—“because that’s where the cheap rents were.” The year was 1998, and my girlfriend had found the place through a broker, who told her straight out, “We’re trying to move white people here.” Less than ten years later, a Richard Meier-designed condominium had sprouted up on the site of an old synagogue at Grand Army Plaza. A few more years after that, “New York’s first steampunk bar” opened a few blocks from my old place.

The units in the Meier building were sold from a realty office in SoHo, which had itself been transforming from a former light-industrial neighborhood with a heroin problem into a chic retreat for couture boutiques by the time that L.A. Times article was published in 1985. The denizens of the downtown art scene who survived and succeeded kept their pied-à-terres well after moving their families to the North Fork. One couple had me score some cocaine to save them the trip to Washington Heights, which now is actually being called WaHi by apartment brokers presumably looking to move white people in.

By then, the only “art” actually still happening in SoHo was sometimes even funded by venture capital like Josh Harris’s legendarily profligate failure Pseudo.com on Broadway. Which is to say, the process of reshaping neighborhood demographics and urban industry was no longer an ad-hoc effort led by a handful of privileged but tolerant middle class white people fleeing the cultural homogeneity of the suburbs. Now it’s funded by institutional investment in startup businesses and real estate development and enabled by local governments interested in attracting the middle class refugees from the rust belt who can afford to relocate and learn professional skills (which all sounded harmless enough when it was called “brain drain” in the old dead tree media).

We moved to Oakland’s Temescal in 2000 largely because it was pretty clear that we weren’t going to make much progress toward any kind of financial security on artist incomes in New York. Here, there was well-paid, if very temporary, web development work for me and a job at a non-profit with low wages but good health insurance for her. We did our part for displacement, certainly, but like the many techies in Silicon Valley’s lower contractor caste who sometimes get to ride the private shuttles, we might have had more stylish lifejackets than most, but we were just trying to keep our heads above water by swimming along with the currents of global capital like everyone but a few.

•••

Let’s go back to that article from 1985, and the plight of the Brandolino family’s experience having to move from their rent-controlled apartment North Beach after “a group of lawyers bought the 17-unit Victorian building in which they had been living to convert it into offices.” They couldn’t afford units in their old neighborhood at the going rate of “$900 or $1,000 a month” on their combined income of $30,000 a year, so they moved to Brisbane—which has no rent control, and could hardly be characterized as “anti-development”—where they found a place for $500 a month.

In today’s numbers, according to the inflation calculator from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, their income would now be near San Francisco’s median around $65,200, presuming it rose in step with inflation (which they haven’t). That would also put the apartments in North Beach out of their reach around $1,950 to $2,150 and the place they found in Brisbane at more like $1,100. But what are rents in North Beach and Brisbane right now? Based on an average of listings, one bedroom units are $2,995 and $1,839, respectively. And that’s assuming the Brandolinos were living in and looking for a one bedroom.

Granted, the average of units in Brisbane is from a very small sample, but again, if the reason real estate developers won’t build is because “the system is intentionally designed to make it as difficult as possible to build new housing,” according to Supervisor Scott Weiner, then why haven’t they been capitalizing on the massive demand by building units in Brisbane? Back in 2006, the suburb was the last stop on Google’s shuttle bus route, and a wave of Googlers were moving in.

But these were people who’d presumably already paid off their school loans and saved a down payment, if not cashed in on the 2004 IPO. The latest generation haven’t had time to make that progress for themselves, and the only they have of doing it is by working themselves to exhaustion at some fly-by-night mobile app startup, so necessarily they’re flocking to the region looking for places to rent. So why weren’t thousands built in Brisbane built during the last boom?

We can look back to that old L.A. Times article for some ideas. The second section leads off with, “a few years ago, there were no vacant offices here. Now, there is a 10% vacancy rate.” What happened was, as the vacancy rate increased, the value of the commercial real estate that companies like CB Richard Ellis were building began to drop. But it was still more expensive per square foot than building in San Mateo County, and because municipalities in California have more to gain for their tax base from commercial development because of Prop 13 restrictions on property taxes, among other reasons, the next twenty years did see a building boom. It’s just that it was corporate campuses and office space sprawling along the peninsula, not apartments.

What housing was built pushed further and further into the exurbs as people chased the home ownership dream, even as transportation costs rose and infrastructure spending dropped. And we all know how well that worked out.

Meanwhile, in San Francisco, real estate developers actually turned coat and allied with planned growth advocates because, by limiting new construction, they could bolster the value of what they’d already built, as detailed in Richard Deleon’s San Francisco political history “Left Coast City.” So the optimism in the following paragraph from our archived article, it turned out, was misplaced — much of these buildings never happened:

The first glass and concrete downtown high-rise sprouted in 1960, [California historian Kevin Starr] said. Now, there are 120 buildings of more than 10 stories in the 470-acre downtown area, with 60 to 70 more expected by the year 2000, the Planning Department says.

Keep that in mind when you read articles from the likes of New York Times technology reporter Nick Bilton, who wandered off the reservation to chime in on local real estate development and parroted pro-development advocates like Wiener’s quote above. Bilton reported that Redfin’s numbers showed homes selling for, on average, 60 to 80 percent above asking. Hard to believe? That’s because it isn’t true, as Priceonomics pointed out. The New York Times had to issue a correction, because in fact over the last two months it’s true that 60 to 80 percent of homes are selling for above asking, but the average premium is only six percent.

Which isn’t necessarily reassuring if your housing is insecure, but it’s useful for illustrating sensationalist bias. Incidentally, Bilton’s characterization of a Tech Workers Against Displacement Happy Hour at Virgil’s Sea Room last week as “an expletive-fueled yelling match between tech workers and people running nonprofits” has been challenged by multiple local reporters who were also there. So when the casual reader at home reads a Gizmodo piece blogsplaining to San Franciscans that we have to build our way out of this mess, keep in mind that you’re basically reading real estate propaganda filtered through two levels of reporters with no expertise on the issue and a pro-development ideological agenda.

The fact is, even if you remove the permitting costs from the process, it’s not profitable to build anything but luxury housing. So no capitalist in their right mind would start building any if they weren’t lured by subsidies, probably in the form of cheap city land or favorable lending rates. The reason no one was building housing during 2009 is because, as you might remember, the entire real estate market collapsed. In fact, the second residential tower on Rincon Hill which is now being finished was already approved years ago but the developer didn’t feel like bothering until market conditions improved (for the developer, not for tenants).

So to review, when it’s profitable to build, San Francisco’s city government has been more than happy help, and right now developers are doing everything in their power to relax building restrictions they themselves supported when the were trying to protect the value of their earlier investments. We can not build our way out of this problem. Besides, even if we tried, the same people will be back to crying for height limits if over-supply or another economic downturn starts to negatively affect prices per square foot.

When it isn’t, rent control can help people stay in their homes, but thanks to vacancy decontrol and the fact that the Rent Ordinance only covers buildings from before 1979, there’s no reason landlords can’t keep up with the market by cashing in on empty units or be discouraged from new residential construction. And almost more importantly than controlling increases, what the Rent Ordinance does and eviction restrictions do is preserve rental stock—something even the market-oriented urbanists at SPUR say is critical right now.

As for the last point, yes, San Francisco has been a witness and participant in the perpetual boom-and-bust cycle of industrial capitalism since 1849. As economies worldwide are forcibly liberalized to a 19th century laissez faire model, wealth has once again concentrated in cities as it did during the robber baron era. In fact, it’s even worse now! And it’s not just happening here.

To review:

- Real wages for the middle class have been declining for forty years.

- The class that has captured that wealth is concentrating in cities.

- The process is accelerating faster than anyone can build.

So yes, this has all been going on forever, and it’s more terrible than ever before. Both!

[Photo: klwang]

Comments (51)

FFS.

“all of which just happen to serve the interests of local real estate developers”

Of course, Jackson. The argument that there isn’t enough housing could _only_ be inspired by a secret conspiracy of real estate developers, and is in no way related to the fact that every new home for sale on any given week in the entire city of SF gets dozens of offers and gets bid up to 50% above asking.

And are you seriously asking why they don’t build south of the city instead? Easy: because those areas can be even more hostile to new development than SF is.

To pretend that the complete infeasibility of moving into or within SF without millions in cash is an imaginary issue, designed to help real estate developers, is ridiculous.

Just open your eyes already and get over your paranoia that somewhere there’s an EEEEEVIL developer that might actually manage to make a buck or two off of new housing, and recognize that supply/demand is totally out whack here. Wiener’s proposal to allow taller development in return for higher on-site BMR requirements is a totally reasonable proposal which will, predictably, be scorned simply out of spite.

And if those builders push for height limits when price/square foot goes down, _then_ you go tell them to fuck off.

And yes, as someone who’s been there, houses are going for way more than 6% above asking all over the place in SF. Friends who’ve been in the market lately have repeatedly bid 15-20% over and lost. If you get something for 6% over, you scored quite a coup.

no conspiracy needed, genius. it’s basic market forces at work.

So from your article, is there any solution to rising costs?

It seems like you want to somehow allow for very strict rent control laws (which we have), so what more is there to do? Even if there was a scheme to allow for people currently renting to remain renting, such as disincentivizing Ellis Act conversions or other things, what we would be left with is a city that will get older and older. The only people allowed to move in will face a tremendous monetary bar to be able to rent here, thus entirely removing the prospect of a new creative class moving here.

So what is the solution then?

To me the solution is to build the hell out of SOMA, the western soma plan is a travesty with heights generally limited to 55 feet (from my recollection). If it’s true that its only worthwhile to build luxury condos then what we want is to move people currently living in what used to be cheap apartments, such as in areas of the mission, to luxury rentals that they can afford. An exodus of people to new buildings, like Nema, will reduce the pressure on exisitng rental stock.

The demand is clearly there for housing, when you have 10s of thousands of people move to a city in a decade but only a few thousand units built, the issue becomes fairly clear. Furthermore when you have a region with cities like Mountain view that have 50% more people working in it than available housing, how is that not a building issue?

my lazyweb dream: a spreadsheet with jobs-to-housing ratio for every major bay area municipality.

I’m not against building, but I am against unplanned development and relaxing development regulation in San Francisco specifically in order to address what is a regional issue, because neither will put a dent in housing affordability.

I agree that development on the Peninsula, Marin and East Bay can be as, if not more, restricted. But where’s the discussion of the Eastern Neighborhoods Plan, or Plan Bay Area, or the opportunity for fresh approaches to municipal development afforded by the dissolution of redevelopment agencies statewide.

Frankly, I’m not sure there is a “solution.” It’s a process! But deregulating development or giving height variances to politically-connected real estate developers in San Francisco probably isn’t it.

We don’t have anything resembling “unplanned” or “deregulated” development; we have the exact opposite. Jesus, how long has it taken to get a single former KFC on Valencia replaced with something that has always complied with existing statutes and was no taller than anything around it?

This sentence really left me scratching my head. Why would this be the case?

Interesting, hadn’t considered that one.

But I wonder if it’s a NIMBY issue as well – most of the Bay Area isn’t mixed-use, particularly when it comes to offices and housing. NIMBY types tend to not want anything built near where they live, but they rarely care if another office building goes up near where they work.

Pretty sure that’s also correct! Because of our home ownership fetishization, and the fact that as a class they are wealthier and less transient than tenants, gives them disproportional political power in local matters. (Their concerns are also disproportionately represented in statewide matters by extension.) Part of the reason Prop 13 is such an electrifying third rail.

Homeowners may have more potitical power on a state-wide level, but they certiantly do not on a local level here in SF.

Pedantic point of mine that bears repeating: Rent control doesn’t mean frozen rent. Your rent still rises in accordance to how it would in the average market. Some years, it still makes a huge dent in your budget.

yet the annual rent control increases are lower than inflation…

A typical wage increase, and social security cost-of-living adjustment, is also lower than inflation.

Besides, I just like to remind people that rent control does not mean frozen rent. Each January, my budget takes a significant hit ($40-$85/month).

You have described a lot of the challenges and macroeconomic forces that make it hard to afford to live in San Francisco, but what you have missed is why developers only build in boom markets here (and why the second tower at One Rincon went on hold). The uncertainty in the process makes financing pre-development nearly impossible here because the City makes it far too easy for NIMBYs to stall projects on a case by case basis. One the other comments mentioned the KFC site on Valencia. If someone proposes a project that meets all of the zoning requirements, and locates their affordable housing on site, there should not be a process for the neighbors to stop the developement. End of Story. It should not have to go through years of redesigns and endless appeals. Regulation is not necessarily a bad thing but inserting an absurd about of subjectivity is not helping anyone (except existing owners, whose home prices are soaring) and is not leading to a better city. Yes, cities are getting more expensive everywhere, but all we have to do is look north to Seattle: they have a very similar hot economy with tons of tech jobs but they have built far more housing than we have, and as a result housing is substantially cheaper (while still out of reach for a lot of people, admittedly).

You linked to my SPUR piece about costs and I think we’re probably on the same page about a lot of things, but it REALLY IS a lot harder to build housing in San Francisco than it is almost everywhere else in the United States. I agree that it is a regional problem, not just an SF one, but we need to accept the fact that this is a very desirable place to live and we can’t stop people from moving here. 24 year olds don’t move to the Bay Area to find a one bedroom in Brisbane.

I respect that it’s very desirable. I mean, I moved here, and I sure as hell don’t want to leave! And I think my point is that sure, it is relatively more difficult to build in San Francisco (though I’m pretty sure infill development is a difficult task contingent on many layers of bureaucratic and neighborhood approval in any highly-dense urban geography, hence my comparisons to New York). But it is not “Impossible.” When I hear hyperbole like that, it serves to remind me that this fight has been going on long before Silicon Valley was even a thing, and long after Bitcoin is a punchline no one gets and Facebook has fizzled into MySpace, and then Friendster, a 150-year old Walter Shorenstein powered by Genentech brand Anti-Aging Creme™ will probably still be funding local political candidates to push whatever party line feels profitable.

Every politician is looking to capitalize on the climate of fear and frustration right now, and just like some are pushing for Ellis reform, others are pushing for eased development regulations. And neither of them are going to address the problem, ultimately. I get that people in the tech industry are pretty defensive right now, but they are also incredibly naive to the history of development battles in San Francisco, and easily duped into advocating for real estate developer interests by proxy because of their shared free market-friendly, public sector-allergic philosophical outlook.

But I’m not sure those old money interests are necessarily the interests of your average 20-something mobile app developer in the long term. In fact, as we’ve seen over the last thirty years, except for a few outlier success stories, the creative classes are usually displaced themselves shortly after being sent in to colonize a “blighted” neighborhood. Maybe other people love the the shiny, new New York City, but as tourist-friendly as the Lower East Side is now, it’s not like any actual artists can afford to move in there anymore. Great place to have a nice meal and get drunk! But is that what we want for the Mission and other eastern neigborhoods?

(To be fair to Wiener, I agree with his reasoning on the recent Golden Gate Bridge toll increase and lament that his proposal wasn’t adopted.)

That article from 1985 really does sound like it could have been written today. Of course, the numbers are a little different:

“Lapping and his wife, a doctor, paid $145,000 for a two-bedroom home in what was a few years ago a blue-collar, Latino neighborhood, Noe Valley.”

First, I want to say that this is the most well-written and informed post I’ve read on this blog. The commentary has (so far) been civil and constructive, as well. Cheers to you for that.

With that out of the way, I disagree with you that we shouldn’t build more in SF just because this is a regional problem. We should absolutely build more here, as it’s an improvement over the status quo. I don’t care that it will make developers more money - this isn’t a zero sum game. More housing (even luxury housing) will take pressure off the rental market, on the margin.

Someone above me brought up the travesty that is the Western SOMA Plan. I can’t believe that one of our most central neighborhoods, which is absolutely surrounded by public transit options and is a stone’s throw from our CBD, effectively consists of of 3-story warehouses, suburban-scale condo complexes, and the occassional converted office building. Issues of massive resident displacement, neighborhood character change, and the like don’t exist here, and yet our Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors still won’t allow any real development in the district.

I’m glad people are starting to finally talk about zoning in this city’s central districts. Upzoning SOMA is a total no-brainer in my mind.

I agree that building in neighborhoods that haven’t historically had a lot of residential stock would be preferable to building in neighborhoods that do, especially when the existing stock is rentals and the new stock is condos. I regularly run through the Dogpatch, and really have to wonder why the condos keep popping up on my two block walk to Four Barrel (three in the last two years) and not on 3rd street south of Mission Bay. Frankly, I thought that was the whole point of the T-Third!

In the case of SOMA, a lot of that actually did used to be residential. The Moscone Center and related development took out a lot of SROs and other housing in the 80s. As for what has gone up around South Beach? Well, when was the last time anyone who didn’t live there think to themselves, “what a pleasant, culturally vibrant neighborhood, I should go spend a weekend afternoon there!” Never. That has never happened.

(24 Willie Mays Plaza, on the other hand, is a magnet for people from around the region. And as someone pointed out to me last night, that project was shot down by voters twice before it was finally approved, and it’s a gem.)

My goal was just to shoot down some somewhat spurious arguments. I’m even open to talking about reforming the Rent Ordinance, but only if Prop 13 is also on the table. What I don’t want to see is a rush to redevelop neighborhoods like the Valencia and Divisadero corridors into SOMA or Mission Bay look-alikes, because they may be hot now, but they wouldn’t necessarily be after that, and we’d have essentially liquidated the value of our existing communities.

The ball park ballots were defeated twice becuase they were huge giveaways to the Giants’ owners. The 3rd try reduced the city’s contribution to a level people found agreeable.

Building along the T line would be great. But the point of building along the Mission-Valencia corridor and on Market st is City Planning 101: you densify along the transportation corridors, so that you can move the people who live there without cars. If you build BART, then you have to connect the people in the city to BART. You do it the Daly City/Ashby way by putting a large parking lot, or you do it by putting the people near the BART station. SOMA is a good example of this, where you put development near Caltrain. The problem with SF is that there are few transportation options… I wish there was a will to connect the western part of the city with better transports.

I will disagree with the point that Prop 13 incentivizes the cities to focus on commercial development. If I ran a city and I had my property tax revenue to grow (which I would need because my costs for services would grow) and Prop 13 would cap what I could grow from the existing built, then I would look for building new stuff. The only problem is that NIMBYism gets in the way, as the people who live there want to preserve the character of their hamlet and want scarcity in the development to increase their property value. Commercial is easier, as it comes with the excuse of jobs and people from elsewhere spending their $ in the community.

Look at the commenters in the Mountain View voice to see what I mean:

http://www.mv-voice.com/print/story/2012/07/13/google-housing-axed-in-ci…

I think you’re really off the mark on your perception of rent control not having a significant impact on sky high rents. And it’s not just the “poor artist or brown person” that has RC since 1985 and pays $800 for a $3500 flat. It’s the well off tech guy who rented a 2br 3 years ago and pays only $2500 for a$3500 flat. Now even THAT GUY has no motivation to leave his flat. There are so many people in SF now that have below market rents, that it causes tremendous distortion to prices for the small number of vacancies that do open up. Hello people! This city desperately needs to means test RC, and stop giving artificial price breaks to anyone that’s been in their place for longer than 2 years.

My rent controlled place was what allowed me to save up the down payment for a condo over these past several years. Now you’re all stuck with me yelling at you about the city’s ridiculous, reactionary, xenophobic development policies for life.

Mwhahaha.

Well, I’m sure your landlord threw a party when you vacated. I just did when my $2700/month tech guy gave me notice that he’s moving in with his GF (thank god for the GF :) Paarrttaaayyyy!

They’ll never means test rent control. Such a change would be a political impossibility. Far too many high income people benefit from the current “seniority” system.

I’ve always considered trying to get a ballot initiative to effect something like this. But I wonder if this is on shaky legal ground and it’s only something the state could do. As a lawyer one day I’ll investigate it.

The point of rent control isn’t to provide some imaginary, racial-based rent protection. It’s to prevent landlords from price gouging. If you’re going to argue against rent control you need to do so on its merits as a consumer protection law, not on some arbitrary goals you’ve made up.

1- my “” was just an anecdote, to show that wealthy people ALSO benefit from RC.

2- LL gouging? Familiar with a free market? Don’t like the rent, don’t rent. Rents are high ONLY BECAUSE so many people hoard low rent units, effectively keeping them off the market.

3- LL gouging? No sir, it’s more like tenant gouging LL! see my response below to Doug Mayer.

Yes, I am familiar with how a free market works. The result of a free market is not necessarily the desired result – kicking people out of their homes just so newcomers can have lower rents is not a “desired result.”

Destroying a community just so a landlord can buy an extra luxury car is completely unacceptable.

Why would anyone be kicked out if they are not getting an artificially low rent? Explain.

Thank you so much for publishing a good piece journalism with discussion of policy set in real world context. Thank you!

Great piece. One thing that gets lost in discussions of “average rent” is exactly where the gap is. San Francisco actually does a halfway decent job of building low-income housing. Rent control combined with requirements for developers to build income-targeted housing (or contribute to the fund) actually works.

It’s middle-income that’s the problem. And no one, as far as I can tell, has a credible plan for fixing that. San Francisco’s official plan[1] is to provide affordable housing to middle income people via market rate housing. Really!

So how do we force the peninsula to build more housing?

[1] http://www.sf-planning.org/ftp/general_plan/I1_Housing.html

I should’ve bought a place in Brisbane when I could’ve afforded it 15 years ago. Now you are stuck with me in my RC 3BR on Valencia for which I pay 1,400 a month. I cannot be Ellised because it’s a multi-unit (Victorian) property owned by a rental management firm. I cannot afford to move, and likely never will, with the rising costs of EVERYTHING, I am stuck here and I hate it.

I’m still confused though. The 3 points that you are considering are: it’s hard to build in SF; rent controls put upward pressure on rents; SF keeps evolving.

Well, yes, yes and yes.

But the data you are showing are on a different plane: erosion of the middle class, changes in who capture the created wealth. Are you trying to say that the 3 points above are a minor factor and the bigger trend is in the post-Reagan growth in inequality?

If so: YES. But the question for SF is: what can we do about it? I could imagine a few answers.

- regarding building: the city should be more affordable housing. Its record is very poor. Abysmal. (which is why politicians posture so much on the Ellis act, even though it won’t make a dent in affordability. They want to “look decisive,” they are “taking action” and mostly they want the media to look some place else. It works!)

- regarding rent control: it’s begging for reform. It protects the twitter millionaires, and many people use rent control as a way to set aside a down payment for a house (oh the irony: rent control as a subsidy for the rich to save to buy real estate to jack up the prices of housing in SF). I would trade off on letting rent fluctuate with assistance for those in need. At least, a poor person could move in this town, instead of the slow exodus of the low-to-middle class.

Yes, change rent control to some sort of rent-surcharge funded subsidy to those who need it. (this coming from a condo owner who actually benefits from rent contol pushing up market rate rents)

This is definitely a better approach than means-testing rent control, which sounds nice to those who haven’t considered the extra incentive it gives landlords to discriminate against lower-income tenants.

The worst offenders are from the older tech companies like Apple and Google. Some of them have lived in their apartments for over a decade and pay significantly less than what everyone else must pay. Somehow, the current law allows this.

I know of one that has already saved a considerable downpayment, but is trying to game even more money from the owner. It’s legalized extortion.

Yes, exactly! It’s like the landlord gets double donged. First, tenant saves lots of money every month by paying below market rent…saving money for a downpayment. THEN tenant extracts a buy out from the LL…maybe to pay for new furnishings from pottery barn, or up the downpayment? WTF people!

GREAT article, without bias! Thanks for some real reporting.

I remember when a movie used to cost 5 cents. True story.

Excellent work. I’m adding comment figuring you know, and a few posters too, that the subject is so intertwined with fed state and local politics,and race and class, and history since WW2, including the massive subsidization of real estate speculation, that the rent control vs build build argument is a foolish trap. There has NEVER been new housing built affordable for working class people . ALL affordable housing was either old stock, or subsidized/mandated by goverment. This is one fact that the build build people will never admit. And the speculators jump from one bubble to the next. Look at the comments on Socket. The bubble gamblers live in a bubble world. Outside of the needs and reality of building truly dense cities. Their density is towers for the 10%. Ours is 3 to 5 or even 8 levels of affordable flats and housing integrated with affordable retail and even light industry. This does not happen in the USA. This is ‘socialism’, hampering the beautiful casino ‘free market’ of developers, who are actually working under a vastly subsidized federal control. For instance, how many regular people know that, if a rich person buys a house on 24th street, lives there for two years, and under this boom, then sells it, and up to $200,000 is fucking tax free. What tenants, workers get such tax free gifts? NONE. Then there is the mortage deduction. Yes, oh yes, pity the poor landlord.

I think you have to own the place for 5 years to get the tax deduction in addition to living in it at least 2 years. And it’s up to $250k for a single/$500k for a married couple.

But technically, since there is an occupancy requirement, it’s not really a gain: if you buy a house, and live in it, and then sell it, well you have to buy another place to live in. If you assume a hot market such that the property on 24th st appreciates by 20% in 2 years, then you’ll have to buy in that hot market when you sell it. So whatever gain you have on the old property disappears into the new property market price.

Also, regarding your last sentence: the landlord does not get the mortgage deduction, that’s only for home ownership. If the landlord carries a loan, then the interests on the mortgage is a cost of doing business, and like any other business, he gets to subtract it from the revenue. But that’s typical business accounting, landlords do not have a particular status in this regard.

It’s true that renter have to pay their rent with post-tax money, which makes it more expensive. But that’s not the landlord’s fault, it’s the tax code.

I agree. Hate the game, not the player :)

200k tax free is not a gain? Us workers are taxed at 15% to 28% in real terms. On every dollar we labor for. Are you trying to tell me that sitting in a house is labor? Is productive to a society? If you’re just flipping in two years? That ‘typical business accounting’ is somehow just? That landlords and the HUGE speculative real estate orgs don’t pay off politicians to keep the tax code this way? That tax code is just something that ‘is’ and not bought?

Don’t forget we have prop 13 too…

Guys, supply and demand is a really simple concept:

But San Francisco is SPECIAL, donchasee! We’re somehow magically exempt from the axioms that govern human behavior everywhere else on the planet. Now stop all this building and give me $500/month rent in perpetuity, please.

Here is a table showing that rents in the Bay Area have diverged from the national average since the late 1950s. I hope that it is readable. New construction helps, but it is simply not possible to stabilize rents in the central Bay Area with new construction. As Saiz pointed out in the Quarterly Journal of Economics a few years ago, the Bay Area is severely geographically constrained compared with most other metro areas. Indianapolis or Houston can easily build out in all directions. A 50 mile radius from downtown San Francisco is 75% either under water or steep hills where you can only build expensive single-family homes. (Of course, there was that idea about creating more land by filling in the bay).

When the market is so constrained, it generates major increases in land value and land rent, resulting in windfall profits for real estate investors. Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations (the founding book in market economics, published in 1776, see “Taxes on the Rent of Houses”) distinguished between the “building rent” that is actually necessary to profitably operate and maintain rental housing, and the “ground rent” that is the extra rent resulting from demand for a particular location. He pointed out that the land rent can justifiably be taxed heavily because the value of the location is created by the larger society, not the landowner. This is called land value taxation, and is generally conceded to be one of the most economically efficient taxes. If instituted taxes on increasing land values could generate enough money to at least mitigate the harms caused by out of control “economic rent”. However, it is not allowable under Proposition 13, which is designed to protect windfall profits from real estate investment under the guise of protecting homeowners.

Looks like the table didn’t post for some reason.