— By Jackson West (@jacksonwest) |

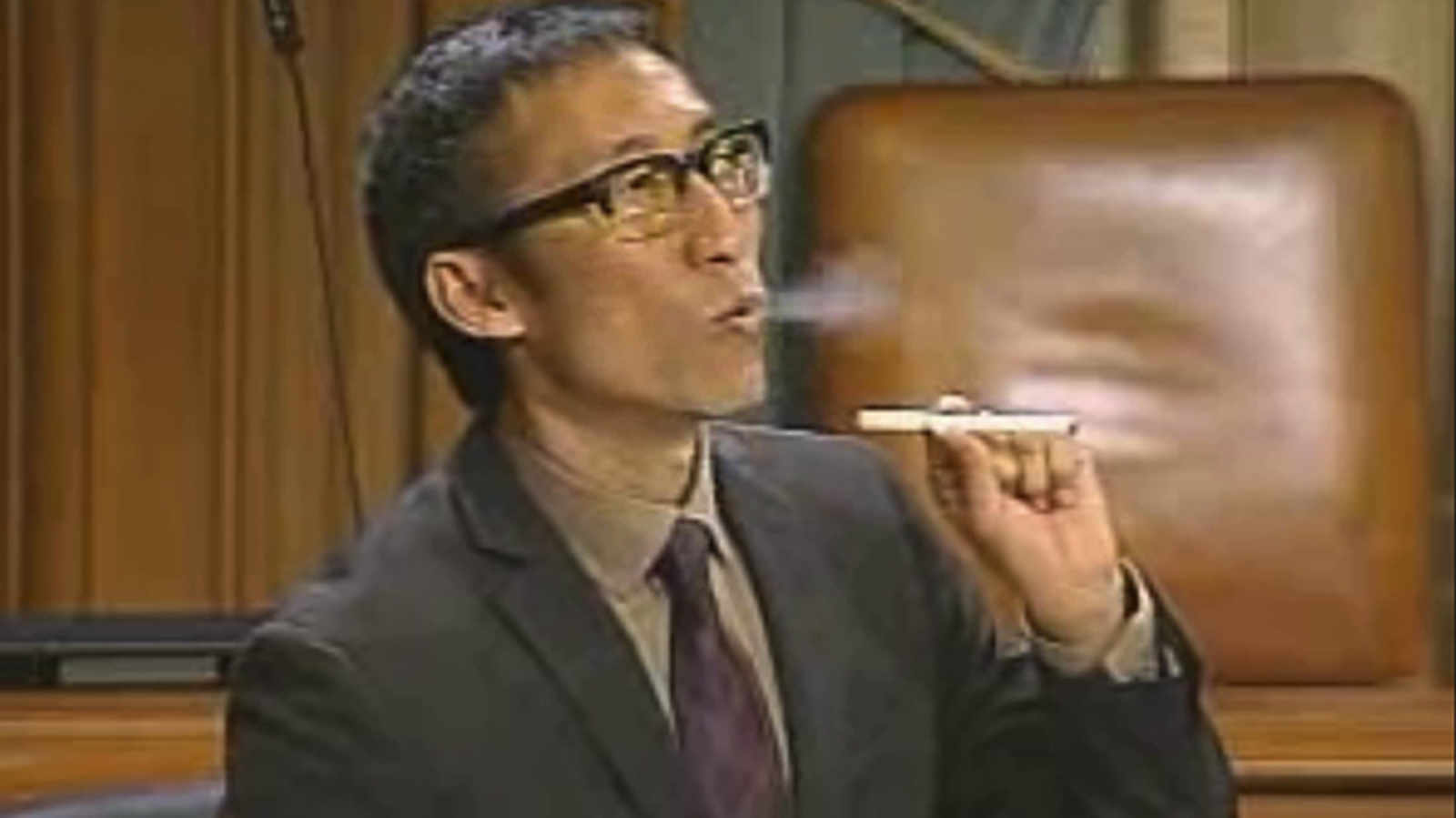

On Tuesday, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to approve an amendment by Supervisor Eric Mar to the city’s health code that will effectively ban e-cigarettes wherever smoking is currently prohibited, which includes most publicly accessible indoor areas, areas around building entrances and windows, and city parks. Mayor Ed Lee has voiced his support for the proposal, meaning the law will likely come into effect within the next few weeks.

Nicotine replacement therapy to treat addiction is an established practice considered very low-risk with ample long-term data. It’s obviously too soon to have any long-term studies on vaporized nicotine yet, but there are plenty of indications that the route of administration offers significantly reduced risks compared to smoking. And that’s not just according to device manufacturers like Mission-based Ploom. This may be a unique opportunity to significantly reduce smoking-related illness, the number one cause of death in the United States. If the goal of amending the Health Code is to reduce the impact of smoking, why is San Francisco actively discouraging alternatives?

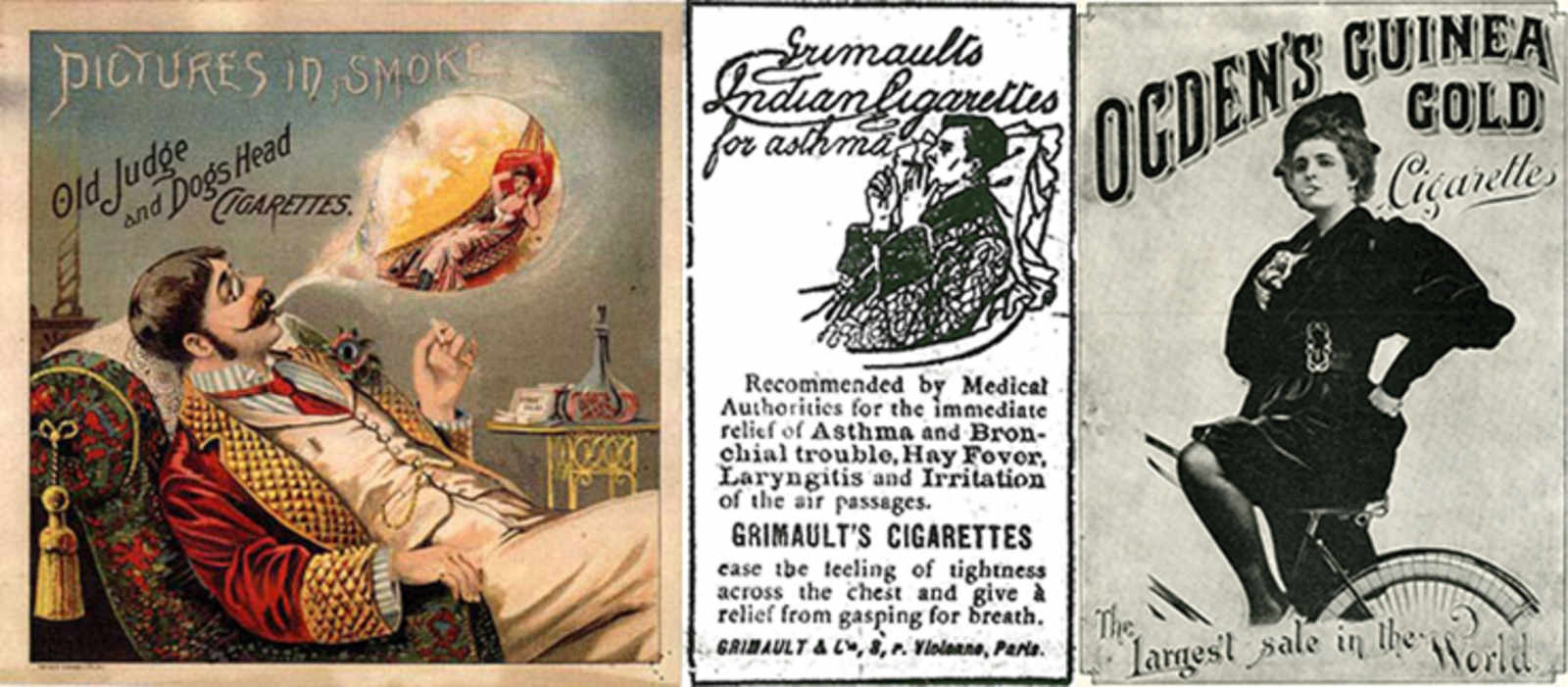

“You must have a cigarette. A cigarette is the perfect type of a perfect pleasure. It is exquisite, and it leaves one unsatisfied. What more can one want?” So declares Lord Wotton to the titular protagonist in Oscar Wilde’s fable of aesthetic philosophy and hedonism, The Portrait of Dorian Gray. During the Victorian era, the cigarette became a popular marvel of industrial technology, combining mechanized mass production with a global commodities trade in tobacco to create a product that was simple, portable, inexpensive and wildly, wildly addictive.

In the novel, Gray’s friend Basil Hallward paints a flattering portrait which shows the reality of Gray’s decline, allowing Gray to indulge in a fantasy of immortality. An apt metaphor Big Tobacco’s propaganda efforts throughout the 20th century as the health risks of cigarettes became widely known.

In 1964, the Surgeon General’s Advisory Committee on Smoking and Health formally declared in the United States that smoking cigarettes causes lung cancer. The next year, Herman Gilbert patented “an object to provide a safe and harmless means for and method of smoking by replacing burning tobacco and paper with heated, moist, flavored air.” But it never made an impact commercially, and tobacco companies largely chose to continue the propaganda campaign.

Some product development did take place, and in 1988 and then again in 1994, RJ Reynolds introduced the Premier and Eclipse, respectively, which were an effort to create a cigarette-like experience without most of the carcinogens and external effects like second-hand smoke. They did surprisingly succeed in achieving those goals with a carbon-heated vaporizer technology, but it also never caught on among smokers.

Finally, in 2003, pharmacist Hon Lik developed an electric vaporizer that emitted a nicotine-laced aerosol for Chinese company Golden Dragon Holdings, which later changed its name to Ruyan. The first commercial models were released in 2004, and exported in 2005 and received international patent protection in 2007.

After over a century, a product with much of the aesthetic experience of smoking a cigarette but without much of the mortal danger actually began to catch on among smokers around the world.

At the time, James Monsees and Adam Bowen were students at Stanford’s Joint Program in Design. There they started what became the company and product Ploom as a masters thesis in 2005, which they presented as a prototype concept. “In 2005, my brother was living in China and he was able to pick one up for me,” Monsees explained in an interview at his office, in a building the company incidentally shares with the Burning Man Project. “I’d heard only because we were heavily researching the market.”

It was this huge box, this entire kit. Because there was nowhere you could buy refills for the thing. E-cig liquid you couldn’t buy aftermarket, either, so you had to buy an insane number of cartridges. I think the kit included like 50 cartridges. And the device was like a big cigar, it was not very good. It was the first generation e-cigarette technology that used a true atomizer, it used a vibrating mesh to create an aerosol. Everything you see know is a resistive heating coil-based technology. And it cost, like, at least $300 use for this giant kit. So we got one, and that was my first exposure to the product.

Monsees and Bowen spent two years on further research and searching for investors before raising seed capital and incorporating in 2007. The first product released by the company, the Model One, was a butane-heated vaporizer that uses disposable pods of leaf tobacco. Their next product, the Pax, dropped the pods and switched to battery power but, to be frank, is probably not used primarily to vaporize tobacco. Today you can pick up a Pax along with your favorite strain of medicine at SPARC.

But as the consumer demand for nicotine vaporizers began to become clear, the business interest from tobacco companies also surged. Japan Tobacco International, which owns Camel among other brands, announced an investment in Ploom and a distribution partnership in 2011, the same year the Model One was released. In 2013, the company introduced the Model Two, a battery-powered device specifically for tobacco.

The rapid growth of the market has produced dozens of competing brands and technological approaches. The blu disposable e-cigarette, which uses the more common nicotine solution technology, has become a leader in the American market and was purchased by Lorillard in 2012. A wide variety of manufacturers of vaporizer parts and accessories and nicotine solutions now create hundreds of products which are now widely available wherever cigarettes are sold, as well as through speciality shops and online retailers.

That was less than ten years ago we first really saw these products at all, in any way, and now they’re so commoditized all of the sudden. That is at the heart of why these regulations are so difficult right now, and really why your seeing them at all. I think in time, in another ten years—or less, hopefully, fingers crossed—there will be a heightened understanding of the substantially improved benefits for public health in particular based on that technology.

The Food and Drug Administration first attempted to regulate e-cigarettes as medical device for drug delivery under the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, but that effort was challenged in court and struck down in a decision which held up under appeal. However, the FDA now plans to regulate e-cigarettes as tobacco products under the provisions of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, passed in 2009, and “intends to issue a proposed rule extending FDA’s tobacco product authorities beyond the above products to include other products like e-cigarettes.” The European Parliament is waiting for final approval from member states for its proposed rules, which ban advertising, require health warnings and limit nicotine levels.

Also in 2009, former California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger (a cigar enthusiast) vetoed Assembly Bill 400, which would have declared nicotine vaporizers a federally regulated drug and effectively banned them, but leaving the state free to regulate them as tobacco products in order to bar sales to minors. Assemblymember Roger Dickinson, D-Sacramento, introduced a bill this year to ban all online sales of tobacco products in California, including e-cigarettes, while municipal governments in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles have put bans into place since the end of 2013, when long-time anti-smoking crusader and former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed that city’s ban into law on his last day in office.

At public comment during the Rules Committee hearing on San Francisco’s ban, supporters argued that e-cigarettes are being marketed to children, who might try the devices and start smoking real cigarettes as a result. However, the evidence of this risk was not particularly compelling, no evidence at all was presented of secondary risks to non-users, and the amendment won’t affect marketing or advertising to children or anyone else. But it will shut the window on the opportunity to vaporize nicotine indoors, a liberty that has significantly increases the appeal of e-cigarettes to existing smokers.

Maybe the most significant data point is that only 12.5 percent of San Franciscans smoke regularly according to Doctor Tomas Aragon at the Department of Public Health, and fewer still likely use e-cigarettes, making their concerns as a constituency easy to marginalize. Anti-smoking activists, who could once count on scientific evidence to support their arguments, seem to be leaving science behind in favor of pious zealotry just as technology may have actually come around to address many, if not most, of the negative consequences typically associated with nicotine addiction.

“I think that’s why this is particularly sad that it’s happening here. We’re smarter than this,” Monsees lamented. In his opinion of San Francisco legislators, “They’re moving quickly to adopt something that has just become a trend across major metropolitan areas.” He feels that the city could be leading the way by sponsoring research independent of federal regulators rather than following the crowd. “I don’t think that action like these at the government level in San Francisco are reflective of the generally mentality of San Franciscans — or would be, if people were properly informed.”

He believes there will be a review of any decisions as more scientific research becomes available, and that the government bears a role in conducting that research if it’s going to make policy proactively. “Is there the financial incentive for companies like us, or major tobacco companies, to do that kind of research if it means an open opportunity to sell those products on the market? Absolutely! But are those products needed today? Are they already on the market? Yes. That’s the reality we live in. There’s been a pent up demand for these products for decades.”

Director of the FDA Center for Tobacco Products Mitch Zeller was cited by Monsees as a pragmatist in this regard. Before being appointed in 2013, Zeller was employed at Pinney Associates, which describes itself as a pharmaceutical risk management group. There, in 2012, Zellar wrote an assesment of strategies for continued tobacco control efforts. “Anyone who would ponder the endgame must acknowledge that the continuum of risk exists and pursue strategies that are designed to drive consumers from the most deadly and dangerous to the least harmful forms of nicotine delivery.”

When asked if he feels that Ploom’s products will be target for enforcement as something which “simulates smoking,” Monsees didn’t seem troubled in any case.

I don’t think that it will have a major impact on our business. I think that our products are really attractive to consumers, in particular because, in our view, internally, they don’t simulate smoking. We’re kind of an oddball in the tobacco industry. In that we’re not interested in simulating smoking. What we’re really interested in doing is understanding, from a consumer level, what people like about smoking and giving them a totally new experience that builds on the good stuff and eliminates the bad stuff. In a totally new way, totally different.

In my view, we don’t simulate smoking. But I don’t think that view has much of anything to do with if it will hurt business or not. The reality is, I don’t think it will hurt business because I don’t think people care about this law. I don’t think it’s going to discourage people from doing what they think is reasonable. It does give law enforcement a tool to enforce offensive behavior by an individual when it’s not appropriate.

Wilde describes how Gray’s wealth and incorruptible beauty—the wages of his sins accruing only on the canvas—bought him access both to the base delights of London’s streets and access to the exclusivity of polite society. On the one hand, supporters of the ban worry e-cigarettes will become as fashionable as cigarettes once were if regulations are too lax, turning back the clock on smoking eradication efforts. Whereas opponents hope smokers, who are more likely to live below the poverty line than non-smokers, might be encouraged to switch if offered less social marginalization, legal complication and regressive taxation.

Our products enable more broad use without offending people. There’s no doubt about that. Smoking, it lingers, it leaves walls and floors and desks and carpets smelling like smoke for a really long time afterwards. It’s really easy to offend people when it survives your presence for such a long period of time. And our products don’t really do that, so it’s much easier to be courteous. And that’s what we suggest people do.

While Monsees supports consumer protection regulations, like product quality control and marketing towards children. But his belief is that the market may have already trumped any political fait accomplis. A familiar laissez fair sentiment, but then some good always does survive gilded ages, and it’s not clear which view is the more “progressive” in this particular case. Preemptively legislating etiquette with punitive measures in the absence of facts and possibly at the expense of positive community health results seems at least as, if not more, irrationally exuberant.

Hopefully the next time the issue comes up, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors can put on a science show instead of a morality play.

Comments (2)

I understand vape advocates frustration over this situation. However, there’s some misunderstanding of the public health perspective in this piece.

For starters, there is ample evidence of e-cig companies using the exact same marketing and promotion tactics that tobacco companies used to snare youth 20 years ago. Moreover the “uncompelling” research out of UCSF shows that there is clearly a link between e-cig and tobacco cig use in adolescent (and other surveillance research shows rapidly growth in adoption of e-cigs by teenagers). While there isn’t an identified causal linkage yet (i.e., we don’t know which kids would never start without e-cigs, and which ones would smoke anyway), earlier addiction has always meant more difficulty in quitting.

This piece also acknowledges that tobacco companies are purchasing e-cig companies (or, in the case of RJR and Altria, launching their own), but fails to recognize the degree to which that allows them to circumvent tobacco control laws. Blu/Lorillard openly urges smokers to use e-cigs during the times they can’t smoke; in other words, to blunt the effect of the smoking restrictions designed to promote cessation. In that context, e-cigs would arguably be used as harm promotion. When you’re dealing with powerful and wealthy corporations moving a highly addictive product, the game isn’t so much puritanism as paranoia.

Of course, treating vaping as equivalent to smoking is responding to a move of a bishop with a blow from a blunt object. There should be a more nuanced attempt to prevent leveraging e-cigs to promote tobacco use, and to have quick reactions to demonstrated risks. Not that any of this will really affect e-cigs as an industry. If it brings so much pleasure, who really cares if you have to leave your bar stool to do it?

What? They’re not discouraging alternatives. They’re just making it less easy for you to be a douche and get your fix inside my cafe and classroom. There is a recent study in Munich showing that vaping causes the air to fill with irritants in a short amount of time. Meanwhile jerks are vaping on Bart and planes. If you can get your addiction anywhere, it’s not cessation.