There are three arguments floating around as to why the rent is too damn high in San Francisco, all of which just happen to serve the interests of local real estate developers:

- San Franciscans make it hard to build!

- Rent control actually causes rents to go up!

- This has been happening since the Gold Rush!

All of these arguments hinge on the assumption that what’s happening right now in the Bay Area generally is somehow unique to San Francisco specifically. This morning, an article about the “yuppification” of San Francisco from the L.A. Times, published in 1985, was making the rounds on Twitter, and plenty of people making these arguments have cited it as proof of one, or all, of the above. It certainly does sound familiar!

Whatever its name, its result is spiraling housing costs, clogged traffic, an exodus of middle-class and poor families and declining black and Latino populations. And the trend seems certain to continue despite a new effort by the city to limit growth, restrain housing costs and preserve neighborhoods.

But it doesn’t just sound familiar to San Franciscans, because it’s happening all over the country.

It’s true that by 1985, the impact of the de-industrialization of American cities and increasing income inequality was first starting to reshape the streets and skyline, helped in no small part locally by then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein (who’s husband, incidentally, is investment banker Richard Blum, chairman of the board of commercial real estate developer CB Richard Ellis). Not to mention the economic policies of the Reagan administration, neo-liberalism’s legendary benefactor and hero. Economic policies which have thrived through the following Republican and Democrat administrations, including the current one.

What is new is that it’s accelerating. And as the divide between the haves and have-nots grows larger, the haves are concentrating their wealth and the have-nots are either clinging to ever-more-precarious perches on the one hand and following the money in a desperate search for economic opportunity on the other.

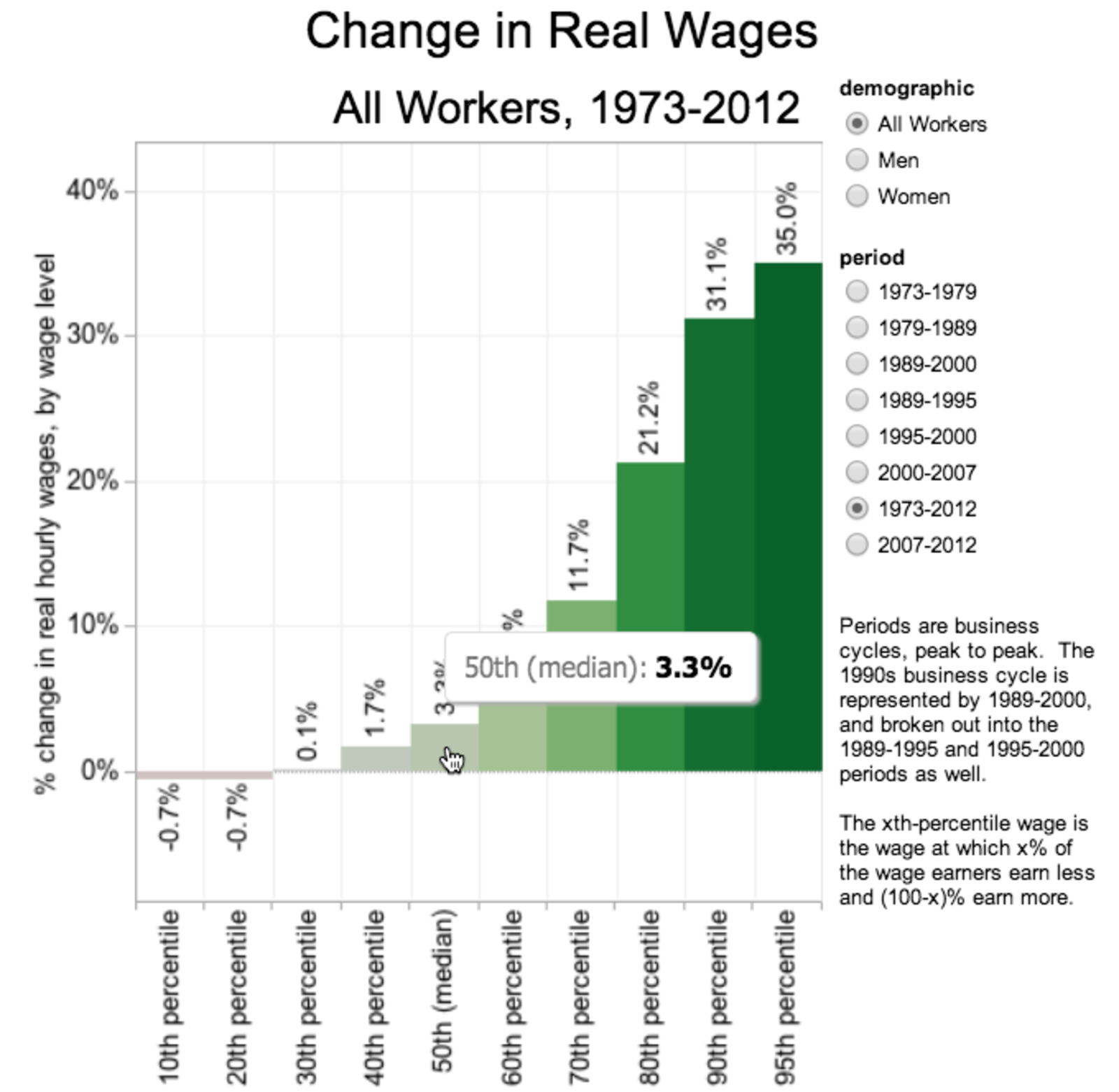

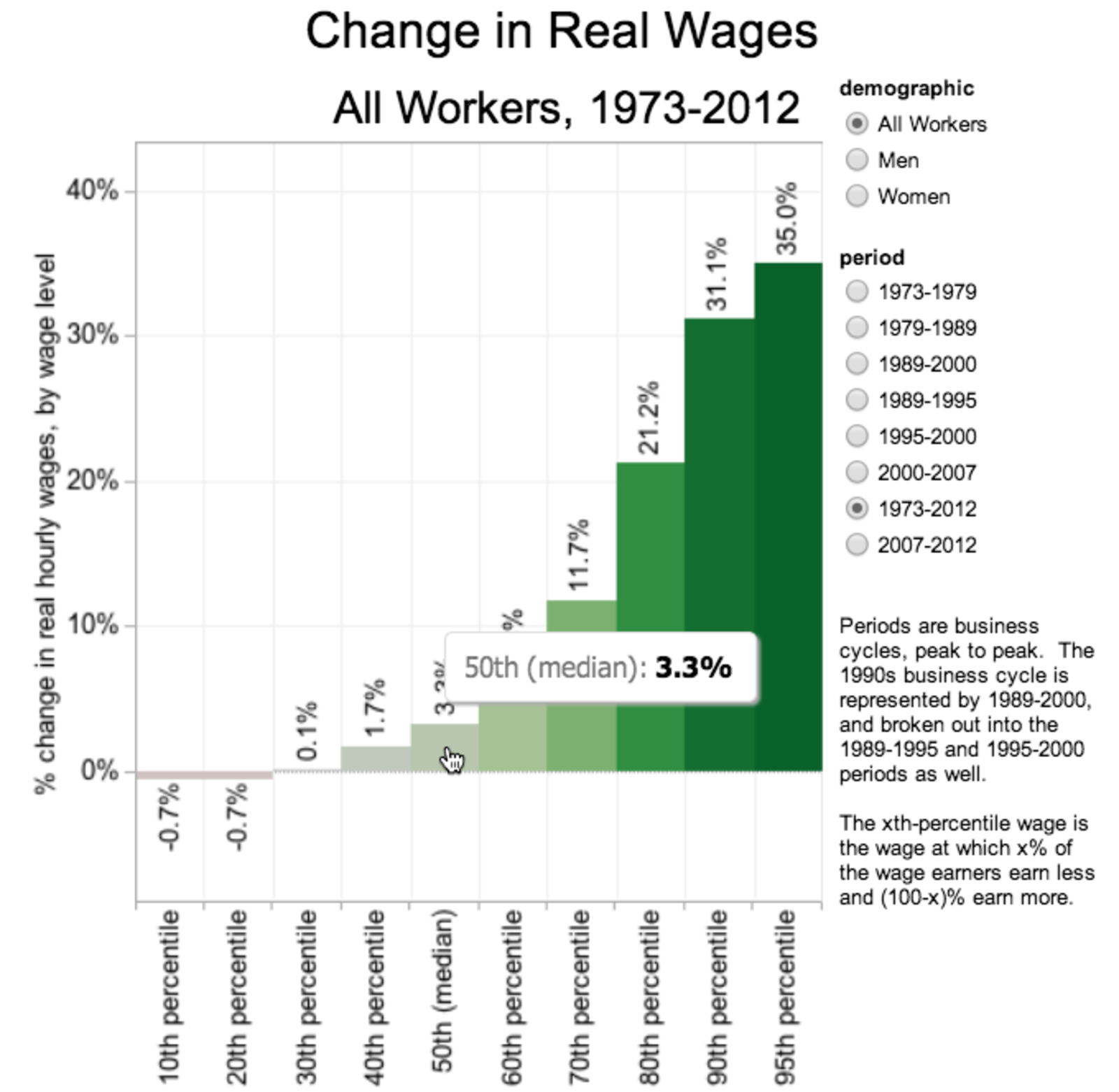

Earlier this week, Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York, a blog which documents the passing of that city’s urban institutions, populations and traditions, published a lengthy article on, frankly, Manhattanization, partly in response to Spike Lee’s recent remarks on what’s happened to the Fort Greene, Brooklyn neighborhood of his youth. It’s as colorful an illustration on the impacts of real wage decline since the 1970s as the above graphs.

Many New Yorkers today, across racial and class lines, do wish for old-fashioned gentrification, that slow, sporadic process with both positive and negative effects—making depressed and dangerous neighborhoods safer and more liveable, while displacing a portion of the working-class and poor residents. At its best, gentrification blended neighborhoods, creating a cultural mix. It put fresh fruits and vegetables in the corner grocer’s crates. It gave people jobs and exposed them to different cultures. At its worst, gentrification destroyed networks of communities, tore families apart, and uprooted lives. Still, that was nothing compared to what we have today.

I want to make one thing clear: Gentrification is over. It’s gone. And it’s been gone since the dawn of the twenty-first century. Gentrification itself has been gentrified, pushed out of the city and vanished. I don’t even like to call it gentrification, a word that obscures the truth of our current reality. I call it hyper-gentrification.

If you want a window into what that earlier era of gentrification looked like, Mission Local also reached back to their archives for an interview with author Michelle Tea about her experience moving to San Francisco in the early 90s (shortly after the Loma Prieta earthquake momentarily relieved pressure on the San Andreas fault, population in-migration, and real estate prices).

Mission Local: Why did you move to the Mission?

Michelle Tea: It’s not that it was a particularly cool neighborhood, although I later found out that it was. This is just where the cheap rents were. I moved here in 1993, and when the bus let me off on Valencia, I remember the street felt deserted — like almost all of the storefronts were closed.

But somewhat tragically, wherever artists and activists go, real estate developers tend to follow, often because they lead the artists and activists there in the first place. Before moving to the Bay Area, my apartment in Brooklyn was at Underhill and Washington Avenue in a community largely composed of immigrants from the Carribean—“because that’s where the cheap rents were.” The year was 1998, and my girlfriend had found the place through a broker, who told her straight out, “We’re trying to move white people here.” Less than ten years later, a Richard Meier-designed condominium had sprouted up on the site of an old synagogue at Grand Army Plaza. A few more years after that, “New York’s first steampunk bar” opened a few blocks from my old place.

The units in the Meier building were sold from a realty office in SoHo, which had itself been transforming from a former light-industrial neighborhood with a heroin problem into a chic retreat for couture boutiques by the time that L.A. Times article was published in 1985. The denizens of the downtown art scene who survived and succeeded kept their pied-à-terres well after moving their families to the North Fork. One couple had me score some cocaine to save them the trip to Washington Heights, which now is actually being called WaHi by apartment brokers presumably looking to move white people in.

By then, the only “art” actually still happening in SoHo was sometimes even funded by venture capital like Josh Harris’s legendarily profligate failure Pseudo.com on Broadway. Which is to say, the process of reshaping neighborhood demographics and urban industry was no longer an ad-hoc effort led by a handful of privileged but tolerant middle class white people fleeing the cultural homogeneity of the suburbs. Now it’s funded by institutional investment in startup businesses and real estate development and enabled by local governments interested in attracting the middle class refugees from the rust belt who can afford to relocate and learn professional skills (which all sounded harmless enough when it was called “brain drain” in the old dead tree media).

We moved to Oakland’s Temescal in 2000 largely because it was pretty clear that we weren’t going to make much progress toward any kind of financial security on artist incomes in New York. Here, there was well-paid, if very temporary, web development work for me and a job at a non-profit with low wages but good health insurance for her. We did our part for displacement, certainly, but like the many techies in Silicon Valley’s lower contractor caste who sometimes get to ride the private shuttles, we might have had more stylish lifejackets than most, but we were just trying to keep our heads above water by swimming along with the currents of global capital like everyone but a few.

•••

Let’s go back to that article from 1985, and the plight of the Brandolino family’s experience having to move from their rent-controlled apartment North Beach after “a group of lawyers bought the 17-unit Victorian building in which they had been living to convert it into offices.” They couldn’t afford units in their old neighborhood at the going rate of “$900 or $1,000 a month” on their combined income of $30,000 a year, so they moved to Brisbane—which has no rent control, and could hardly be characterized as “anti-development”—where they found a place for $500 a month.

In today’s numbers, according to the inflation calculator from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, their income would now be near San Francisco’s median around $65,200, presuming it rose in step with inflation (which they haven’t). That would also put the apartments in North Beach out of their reach around $1,950 to $2,150 and the place they found in Brisbane at more like $1,100. But what are rents in North Beach and Brisbane right now? Based on an average of listings, one bedroom units are $2,995 and $1,839, respectively. And that’s assuming the Brandolinos were living in and looking for a one bedroom.

Granted, the average of units in Brisbane is from a very small sample, but again, if the reason real estate developers won’t build is because “the system is intentionally designed to make it as difficult as possible to build new housing,” according to Supervisor Scott Weiner, then why haven’t they been capitalizing on the massive demand by building units in Brisbane? Back in 2006, the suburb was the last stop on Google’s shuttle bus route, and a wave of Googlers were moving in.

But these were people who’d presumably already paid off their school loans and saved a down payment, if not cashed in on the 2004 IPO. The latest generation haven’t had time to make that progress for themselves, and the only they have of doing it is by working themselves to exhaustion at some fly-by-night mobile app startup, so necessarily they’re flocking to the region looking for places to rent. So why weren’t thousands built in Brisbane built during the last boom?

We can look back to that old L.A. Times article for some ideas. The second section leads off with, “a few years ago, there were no vacant offices here. Now, there is a 10% vacancy rate.” What happened was, as the vacancy rate increased, the value of the commercial real estate that companies like CB Richard Ellis were building began to drop. But it was still more expensive per square foot than building in San Mateo County, and because municipalities in California have more to gain for their tax base from commercial development because of Prop 13 restrictions on property taxes, among other reasons, the next twenty years did see a building boom. It’s just that it was corporate campuses and office space sprawling along the peninsula, not apartments.

What housing was built pushed further and further into the exurbs as people chased the home ownership dream, even as transportation costs rose and infrastructure spending dropped. And we all know how well that worked out.

Meanwhile, in San Francisco, real estate developers actually turned coat and allied with planned growth advocates because, by limiting new construction, they could bolster the value of what they’d already built, as detailed in Richard Deleon’s San Francisco political history “Left Coast City.” So the optimism in the following paragraph from our archived article, it turned out, was misplaced — much of these buildings never happened:

The first glass and concrete downtown high-rise sprouted in 1960, [California historian Kevin Starr] said. Now, there are 120 buildings of more than 10 stories in the 470-acre downtown area, with 60 to 70 more expected by the year 2000, the Planning Department says.

Keep that in mind when you read articles from the likes of New York Times technology reporter Nick Bilton, who wandered off the reservation to chime in on local real estate development and parroted pro-development advocates like Wiener’s quote above. Bilton reported that Redfin’s numbers showed homes selling for, on average, 60 to 80 percent above asking. Hard to believe? That’s because it isn’t true, as Priceonomics pointed out. The New York Times had to issue a correction, because in fact over the last two months it’s true that 60 to 80 percent of homes are selling for above asking, but the average premium is only six percent.

Which isn’t necessarily reassuring if your housing is insecure, but it’s useful for illustrating sensationalist bias. Incidentally, Bilton’s characterization of a Tech Workers Against Displacement Happy Hour at Virgil’s Sea Room last week as “an expletive-fueled yelling match between tech workers and people running nonprofits” has been challenged by multiple local reporters who were also there. So when the casual reader at home reads a Gizmodo piece blogsplaining to San Franciscans that we have to build our way out of this mess, keep in mind that you’re basically reading real estate propaganda filtered through two levels of reporters with no expertise on the issue and a pro-development ideological agenda.

The fact is, even if you remove the permitting costs from the process, it’s not profitable to build anything but luxury housing. So no capitalist in their right mind would start building any if they weren’t lured by subsidies, probably in the form of cheap city land or favorable lending rates. The reason no one was building housing during 2009 is because, as you might remember, the entire real estate market collapsed. In fact, the second residential tower on Rincon Hill which is now being finished was already approved years ago but the developer didn’t feel like bothering until market conditions improved (for the developer, not for tenants).

So to review, when it’s profitable to build, San Francisco’s city government has been more than happy help, and right now developers are doing everything in their power to relax building restrictions they themselves supported when the were trying to protect the value of their earlier investments. We can not build our way out of this problem. Besides, even if we tried, the same people will be back to crying for height limits if over-supply or another economic downturn starts to negatively affect prices per square foot.

When it isn’t, rent control can help people stay in their homes, but thanks to vacancy decontrol and the fact that the Rent Ordinance only covers buildings from before 1979, there’s no reason landlords can’t keep up with the market by cashing in on empty units or be discouraged from new residential construction. And almost more importantly than controlling increases, what the Rent Ordinance does and eviction restrictions do is preserve rental stock—something even the market-oriented urbanists at SPUR say is critical right now.

As for the last point, yes, San Francisco has been a witness and participant in the perpetual boom-and-bust cycle of industrial capitalism since 1849. As economies worldwide are forcibly liberalized to a 19th century laissez faire model, wealth has once again concentrated in cities as it did during the robber baron era. In fact, it’s even worse now! And it’s not just happening here.

To review:

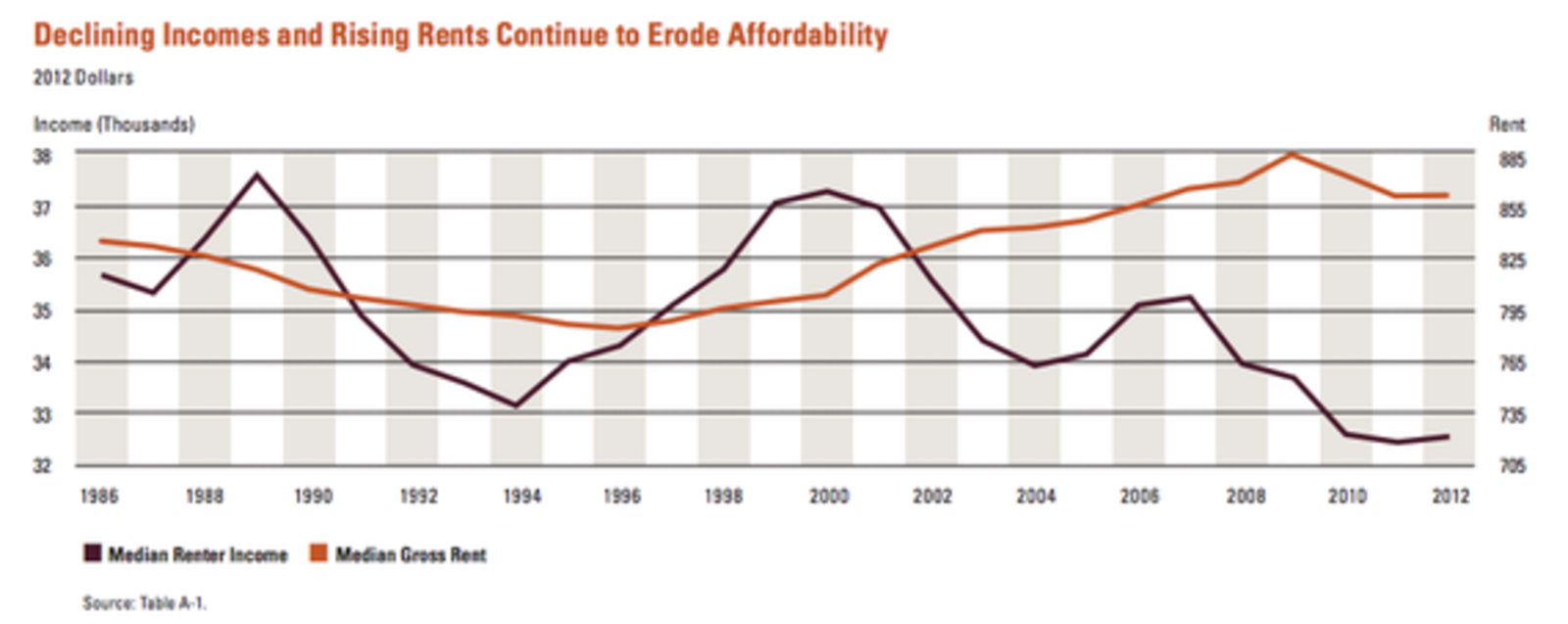

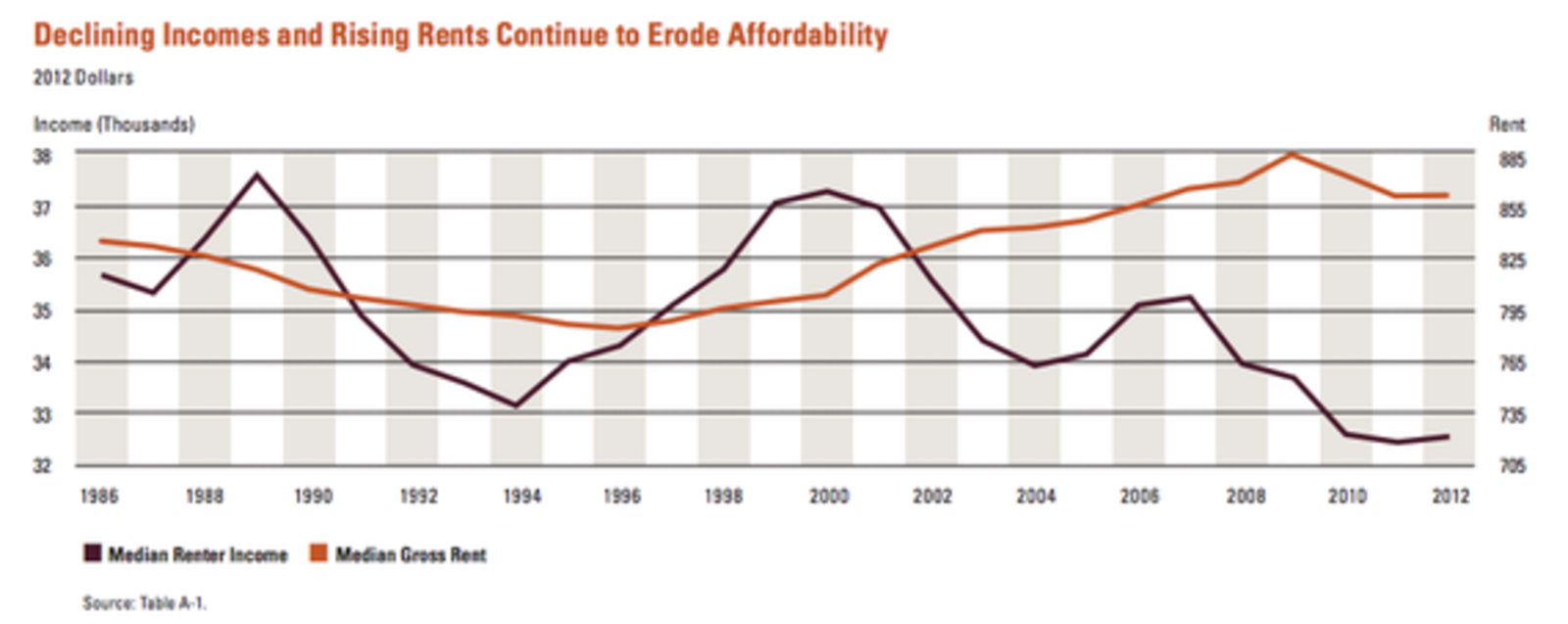

- Real wages for the middle class have been declining for forty years.

- The class that has captured that wealth is concentrating in cities.

- The process is accelerating faster than anyone can build.

So yes, this has all been going on forever, and it’s more terrible than ever before. Both!

[Photo: klwang]